10

numbers on the R.A. setting circle if you’re in the Northern

hemisphere. Retighten the lock knob.

2. Loosen the Dec. lock knob and rotate the telescope until

the Dec. value from the star atlas matches the reading on

the Dec. setting circle. Remember that values of the Dec.

setting circle are positive when the telescope is pointing

north of the celestial equator (Dec. = 0°), and negative

when the telescope is pointing south of the celestial equa-

tor. Retighten the lock knob.

Most setting circles are not accurate enough to put an object

dead-center in the telescope’s eyepiece, but they should

place the object somewhere within or near the eld of view

of the nder scope, assuming the equatorial mount is accu-

rately polar aligned. Use the slow-motion controls to center the

object in the nder scope, and it should appear in the tele-

scope’s eld of view.

The R.A. setting circle must be re-calibrated every time you

wish to locate a new object. Do so by calibrating the setting

circle for the centered object before moving on to the next one.

Confused About Pointing the Telescope?

Beginners occasionally experience some confusion about how

to point the telescope overhead or in other directions. One

thing you DO NOT do is make any adjustment to the mount’s

latitude setting or to its azimuth position. That will throw off the

mount’s polar alignment. Once the mount is polar aligned, the

telescope should be moved only about the R.A. and Dec. axes.

This is done by loosening one or both of the R.A. and Dec.

lock knobs and moving the telescope by hand, or keeping the

knobs tightened and moving the telescope using the slow-

motion cables.

IX. Collimating the Optics

(Aligning the Mirrors)

Collimating is the process of adjusting the mirrors so they are

aligned with one another. Your telescope’s optics were aligned

at the factory, and should not need much adjustment unless

the telescope is handled roughly. Accurate mirror alignment is

important to ensure the peak performance of your telescope,

so it should be checked regularly. Collimating is relatively easy

to do and can be done in daylight.

To check collimation, remove the eyepiece and look down the

focuser drawtube . You should see the secondary mirror cen-

tered in the drawtube, as well as the reection of the primary

mirror centered in the secondary mirror, and the reection of

the secondary mirror (and your eye) centered in the reection

of the primary mirror, as in Figure 15a. If anything is off-center,

proceed with the following collimating procedure.

The Collimation Cap and Mirror Center Mark

Your AstroView 6 comes with a collimation cap. This is a sim-

ple cap that ts on the focuser drawtube like a dust cap, but

has a hole in the center and a silver bottom. This helps center

your eye so that collimating is easy to perform.

Figures 15b through 15e assume you have the collimation

cap in place. In addition to providing the collimation cap, you’ll

notice a tiny ring (sticker) in the exact center of the primary

mirror. This “center mark” allows you to achieve a very pre-

cise collimation of the primary mirror; you don’t have to guess

where the center of the mirror is. You simply adjust the mirror

position (described below) until the reection of the hole in the

collimation cap is centered inside the ring. NOTE: The center

ring sticker need not ever be removed from the primary mirror.

Because it lies directly in the shadow of the secondary mir-

ror, its presence in no way adversely affects the optical perfor-

mance of the telescope or the image quality. That might seem

counterintuitive, but it’s true!

Aligning the Secondary Mirror

With the collimation cap in place, look through the hole in the

cap at the secondary (diagonal) mirror. Ignore the reections

for the time being. The secondary mirror itself should be cen-

tered in the focuser drawtube, in the direction parallel to the

length of the telescope. If it isn’t, as in Figure 15b, it must be

adjusted. Typically, this adjustment will rarely, if ever, need to

be done. It helps to adjust the secondary mirror in a brightly lit

room with the telescope pointed toward a bright surface, such

as white paper or wall. Placing a piece of white paper in the

telescope tube opposite the focuser (i.e., on the other side of

the secondary mirror) will also be helpful in collimating the sec-

ondary mirror. Using an Allen wrench, loosen the three small

alignment setscrews in the center hub of the 3-vaned spider

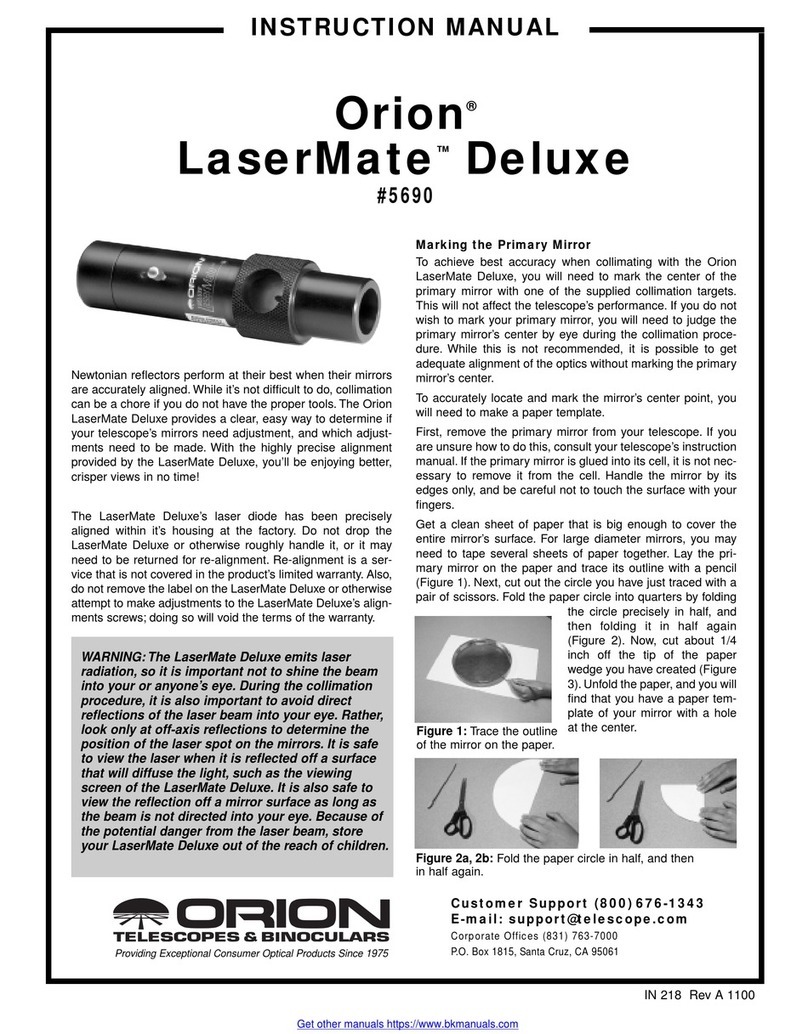

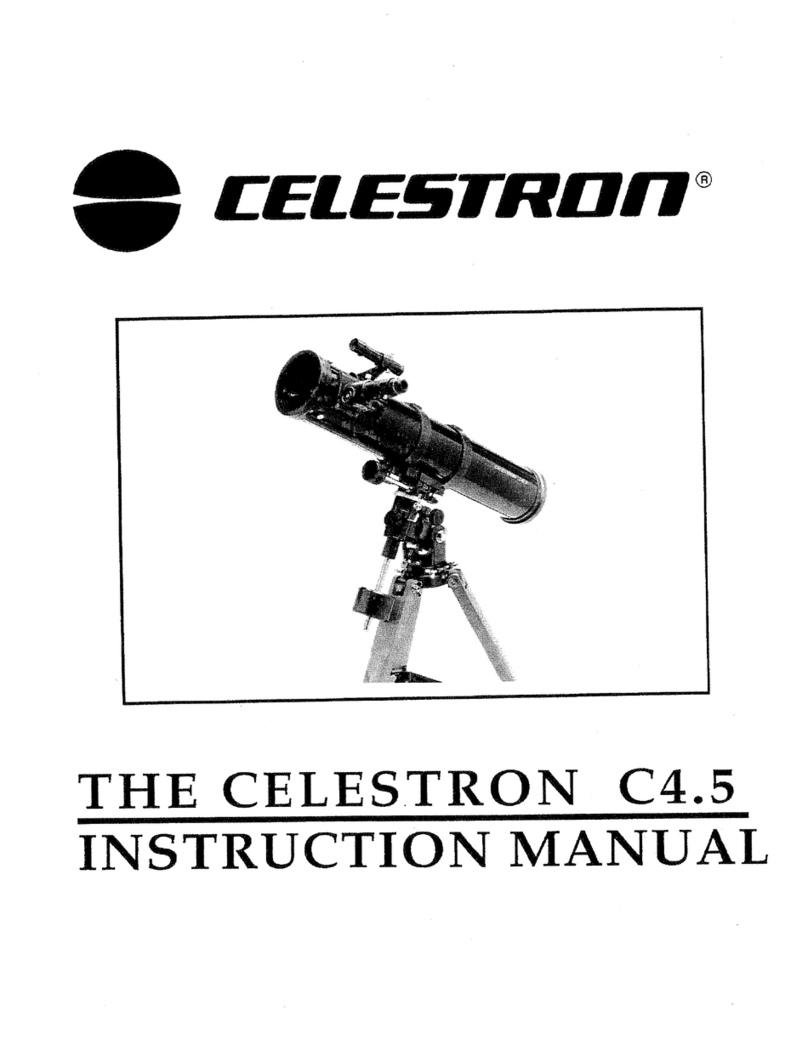

Figure 17. Primary mirror collimation screws. Clockwise around

the perimeter, the left screw in each pair is the "pull screw" and the

right screw is the "push" screw.

Push screw

Push screw

Push screw

Pull screw

Pull screw

Pull screw

Figure 18. A star test will determine if a telescope’s optics are

properly collimated. An unfocused view of a bright star through

the eyepiece should appear as illustrated on right if optics are

perfectly collimated. If circle is unsymmetrical, as in illustration on

left, scope needs collimation.

Out of collimation Collimated