Minimizing Pickup of Nearby Instruments

A significant and ever-present problem in contemporary studio recording is minimizing leakage from

nearby instruments into the various microphones. While gobos (portable isolation walls) can be ef-

fective in isolating performers from each other, they often introduce their own set of problems. To be

effective, gobos are usually very bulky and occupy valuable floor space. They also inhibit the ability

of the musicians to hear each other, thus requiring complex and often cumbersome headphone monitor

mixes for the musicians.

One solution to this problem is to use bidirectional microphones and arrange the musicians so that they

are at right-angles to each other, thus placing nearby musicians in the null of their neighbor’s micro-

phone, and vice versa. Although this won’t entirely eliminate the need for gobos, it will reduce the

number you need. As a result, the studio can be less crowded, and because the musicians now will be

better able to hear each other directly, the need for numerous monitor headphones also can be reduced.

Another common problem in both recording and sound reinforcement situations occurs when a singer

is also playing an instrument, such as guitar or piano. The need to provide good isolation between the

singer’s voice and the instrument usually leads to the use of separate microphones for each, but this can

lead to problems of balance and phase interference between the microphones. In both of these situa-

tions, the use of a single bidirectional microphone can provide the solution.

Vocal ensembles, such as duets, trios, and quartets, also can use these microphones to good advantage

by grouping around the mic and balancing their voices to achieve a proper natural blend. This can elim-

inate the need to rely on a mixing engineer to make them sound right: the musicians do it themselves!

For Announcers, Dialog, and Radio Plays

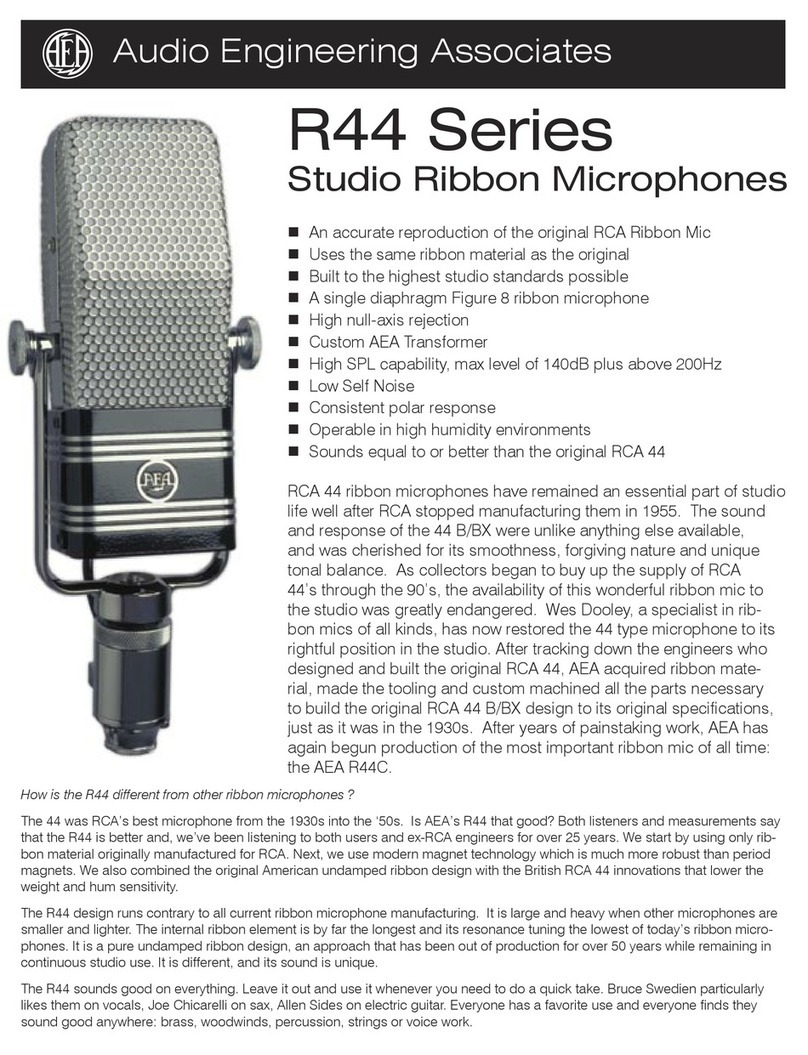

Ever since the “golden days of radio” in the 1930s and ‘40s actors have appreciated working with bi-

directional microphones such as the RCA-44. Not only does this have an unsurpassed quality with the

human voice, the two-sided pickup helped to create the art of radio acting because it allowed the actors

to work on either side of the microphone so they were able to face and act to and with each other. Com-

ing into a scene meant doing little more than starting with one’s head turned slightly away from the

mic and then turning back toward the mic as dialog began. If a more distant approach was required,

beginning the scene just a step or two back and then moving towards the mic would produce this effect.

Coming in from an even greater distance could be accomplished by starting the dialog from the side

of the microphone and then moving around to be on-axis. Throughout all of this, the script could be

held directly to the side of the microphone allowing the actors to read, yet minimizing the sound of the

pages rustling as they were changed.

Proximity Effect

Proximity effect or “bass tip-up” is a characteristic of all directional microphones, but none exhibits

more than the single-diaphragm velocity microphone. In fact, it is the pressure-gradient component in

all directional microphones that renders them susceptible to proximity effect. Pressure response micro-

phones, on the other hand, are not subject to it and retain relatively flat low frequency response at any

distance.

Although this is generally considered the result of working at a very close distance to the microphone,

the AEA R44 and A440 exhibit measurable proximity effect at distances closer than six feet. (ref. Fig-

ure-4) This rising low-frequency response at closer working distances can be used to good effect, par-