Pick up the mast and hold it vertically in the boat with the forestay lug on the

mastband facing forward. Raise it and lower it straight down through the hole in

the thwart, placing the heel firmly in its socket.

To set up the shrouds take one side and pass several turns of the lanyard

through the U-bolt fairlead which is fitted on the side bench. Tension slightly and

secure with two or three half-hitches(Fig.15). Do the same the other side, pulling

the mast central and bending it somewhat aft. Finally reeve off the forestay

lanyard through the shackle in the stemhead fitting and pull it up as hard as you

can before securing. This should tension all three wires and leave the mast

standing straight without bearing hard on the thwart in any direction. Note that

the forestay is always set up to the stemhead and not to the end of the bowsprit.

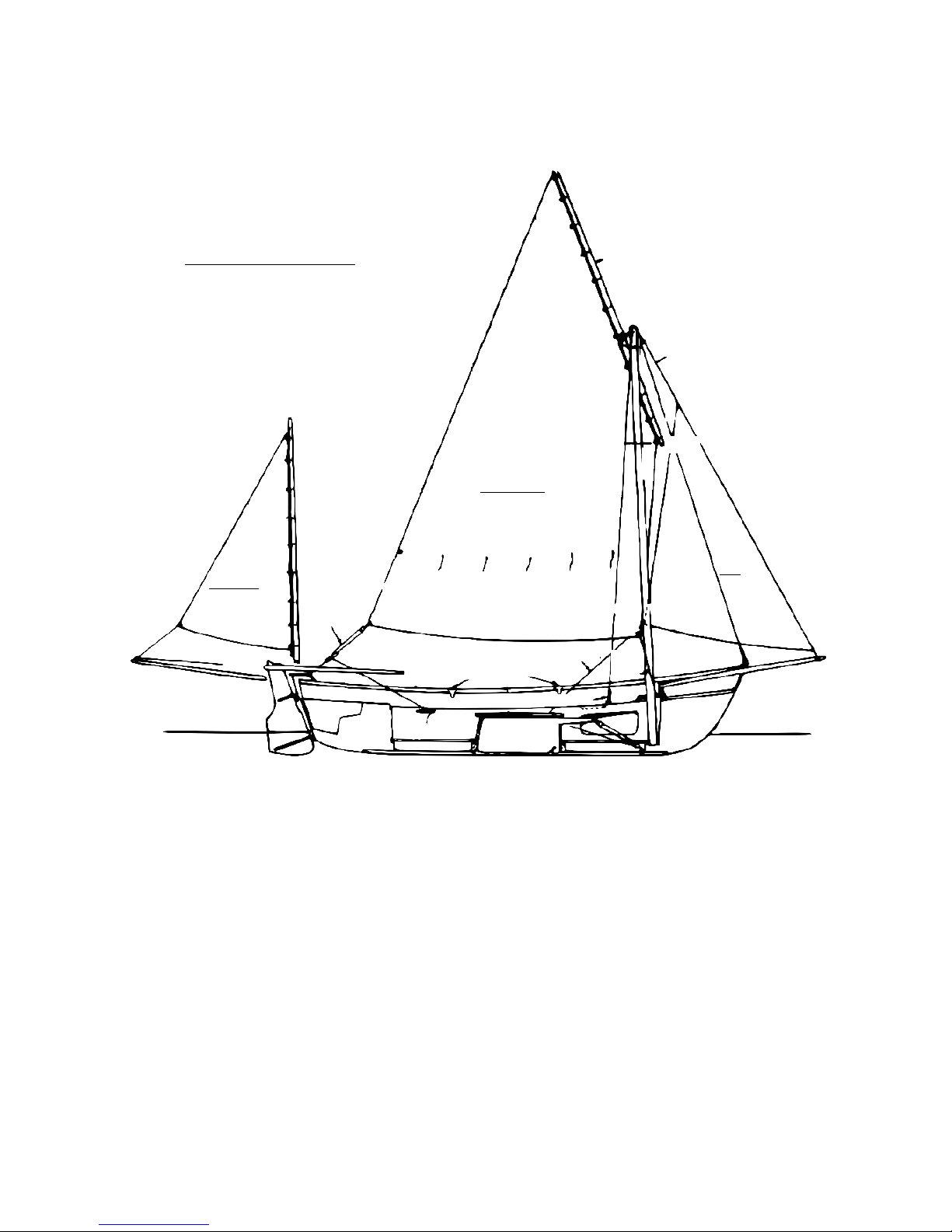

The mainsail has to be lashed to its yard and the mizzen to its mast. The

method is the same tor both. First secure the lower corner (in the case of the

mainsail, the throat cringle to the lower end of the yard) and stretch the sail along

the spar. Tension the top lanyard until the sail shows slight creasing parallel to

the spar and secure the peak. Then lace to the spar with the marlin hitch (Fig.11)

but not too tightly. The lacing is only to stop it from bowing away and should be

slack enough to permit some movement of the sail relative to the spar.

Ship the bowsprit through the hole in the stern and the bumpkin through the

hole in the corner of the transom and you are ready to go. Step the mizzen mast

through the transom cap into in step and tie its sheet to its clew. Pass the sheet

through the bullseye on the bumpkin, back to the clam cleat on the after deck via

the bullseye on the side of the mast. Tie the jib halyard to the head of the jib and

slip the loop at the tack of the jib over the end of the bowsprit. Hoist away on the

halyard and belay to the belaying pin on the thwart with a good amount of

tension. The jib sheet may conveniently be secured to the clew by means of a

double overhand knot as explained in Fig. 5 on Pg. 8. Pass the ends through the

fairleads on the side bench and either put a knot at each end or tie the ends

together.

Ship the rudder in shallow water and fix the tiller by holding the thin end

high in the air while passing it down over the rudder head until it engages with

the notch in the rudder. You may then raise the tiller a considerable distance

before it comes clear of the circular arc on the rudder and hence in danger of

coming off.

After shipping the tiller adjust the length of the mainsheet horse (the length

of line across the transom on which the lower block runs) to give it about a foot

of slack. (Fig. 16).

Before hoisting the mainsail first reeve off the mainsheet (Fig. 16) and

shackle it to the clew but do not secure the end other than with a knot to stop it

from being lost through the lower block. Pass the tack downhaul, which is single

length of line approximately 4ft. long, up through one of the holes in the thwart,

tying a knot in its end to hold it there, through the tack cringle on the sail and

down through the other hole opposite (Fig.12) but do not draw tight. Attach the

halyard to the yard by taking two turns round the yard immediately below the tri-

angular chocks, and secure with two half hitches (Fig.2)

8