Did you engineer those sessions?

Most of them, yes.

What is your engineering training?

Oh, I’m a knob-twiddler. I belong to the learn-by-

doing school.

Have you had any miserable failures?

Yeeeeahhh… actually I had a bad time in ’98. I was up

north in India in Jammu. And, boy those tapes are

distorted. That’s why I really need a distortion

removal plug-in. I was using a [Neumann] KM 84 and

an MKH30 - you know, the bi-directional Sennheiser

-as a mid-side configuration, and the recordings are

dreadful. These guys were singing really loud, and

there was maybe 140 dB SPL. A friend said, “Hmm…

I think it’s the mic capsule bottoming.” But then I

consulted with Klaus Heyne, the mic guru, and he

diagnosed the problem as an overloaded FET in the

KM 84. At times like that, I think, “Gee, I wish I had

somebody knowledgeable along,” you know?

To blame? [laughs]

Yes, or to bail me out! [laughs] It’s hard when you’re

there all alone, trying to handle all of the recording,

the documentation and the photos. And it was

unbearably hot. It was the hot season in Jammu, so

I was sweating profusely the whole time as well.

You’re recording to a DAT now?

Yes. The only DAT recorder that I feel works, if we’re still

talking stereo, is the [HHB] PortaDAT. Maybe the

Fostex PD2 or PD4 are good, but I’ve never used one.

I have a PortaDAT and I really like that. They’re made

basically for film work. The problem is that young

people who want to go off and record just don’t have

$15,000 for equipment - three grand for the recorder

and the extra batteries, which are essential, are 150

bucks a clip. You’ve got to have at least three batteries

and then you need a selection of mics. I have a pair

of KM 84s, a pair of KM 83s, the MKH20, and a pair of

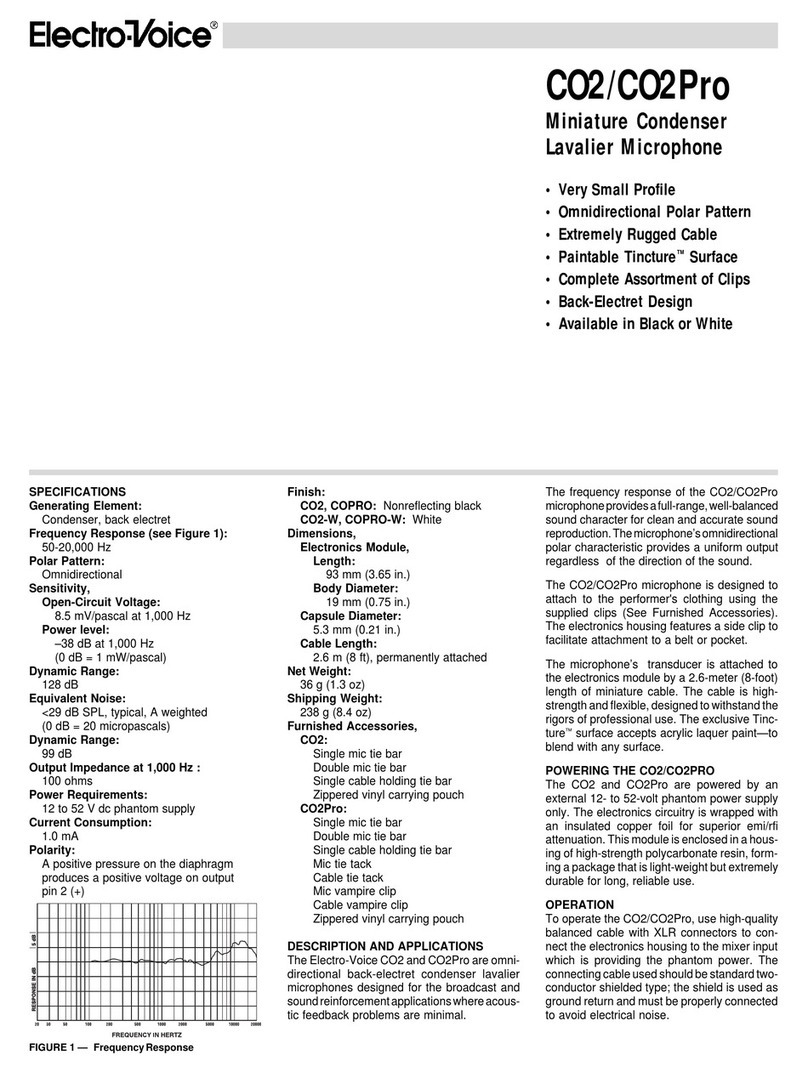

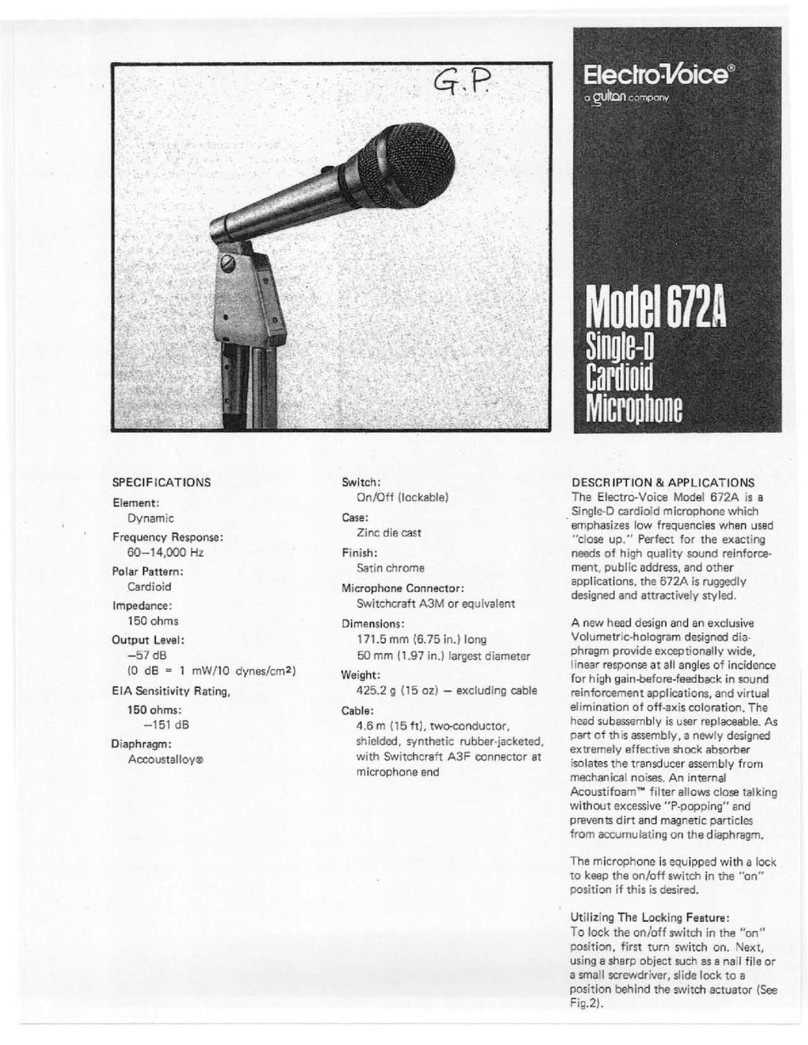

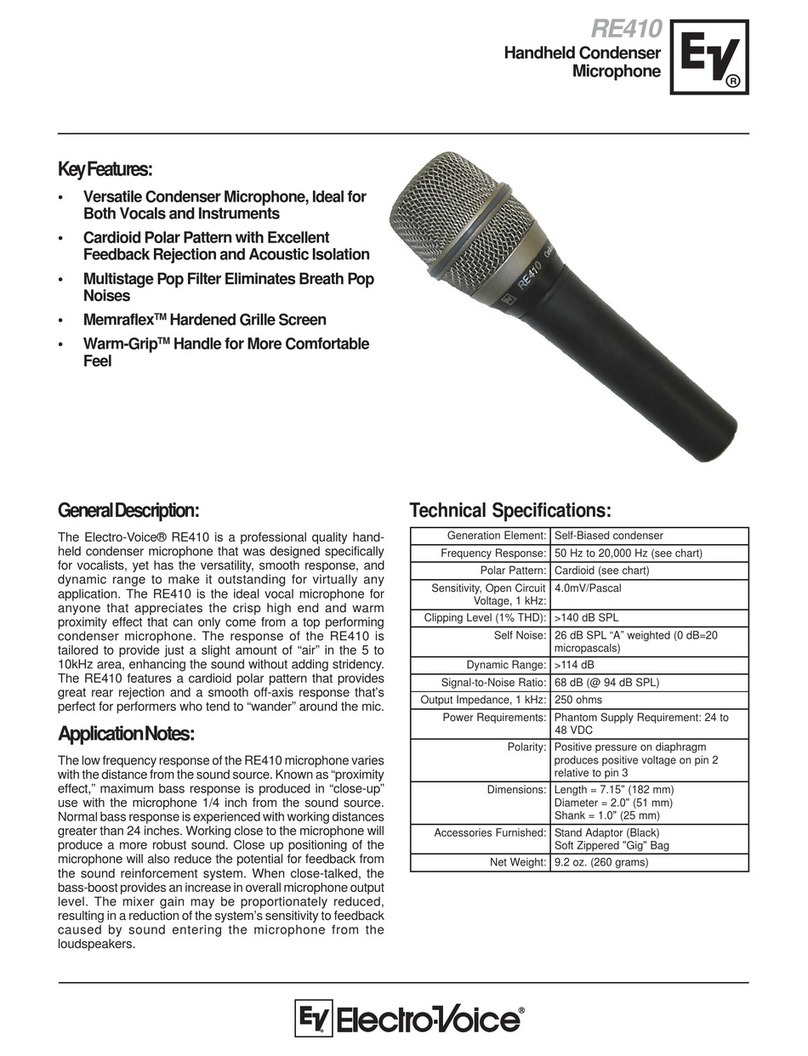

inexpensive [Electro-Voice] RE50s because I find

they’re absolutely well behaved. They’re what I use

whenever I need a spaced pair of omnis, rather than

the KM 83s. In fact, in ‘87 I used only the RE50s in

Bali, and everybody is amazed at the quality of the

recordings. Here I am using a pair of inexpensive

dynamics and the transients aren’t bothered at all.

While this mic has a fairly steep fall off below 100 Hz

and above 13 kHz, it’s perfect for Bali!

Has there ever been an occasion where

the musicians stopped because they

weren’t happy with the performance?

Yeah. Musicians stop from time to time and say, “Wait a

minute, that passage isn’t right.” And then they go

back and do it over. Basically, I feel I’m there to serve

the musicians and to give them the best recording of

their material. And of course, for them it’s a business

also. When I went back again to Bali in ‘94 they were

really pleased to see me because they knew, “Oh!

David pays!” When I’m planning a trip, I always have

to decide what is a realistic sum to allow for

musicians’ fees. What I try to do is to come up with

payment that makes sense within a particular culture.

In Bali in ‘87 the going rate for a session with a big

gamelan was $100. When I returned in ‘94, I sought

out the same musicians because I had enjoyed

working with them, and asked, “Would you care to do

some more recording?” “Absolutely,” they said. And

then I asked them, “How much?” Their response: “The

regular price is $400. But for you David, only $250.”

At that point, I’m not going to insult musicians by

bargaining, right? That would be really low class. So

I either have to say, “Gee, I’d love to. But I just don’t

have the money,” or “Okay. I’ll find the money.” When

I recorded in Kullu in India’s West Himalaya in the

early ‘70s, I met Seshi, a fine musician who was the

staff composer at the AIR [All-India Radio] station in

Shimla. He had some of the AIR Shimla staff

musicians with him. They went to the local festivals

to give concerts and learn fresh tunes from the locals.

We worked together to make recordings in Kullu, and

his gifts were clearly evident. He’s really able to

inspire fine performances. So when I went back to

Delhi a few years ago, I rang his house, was delighted

to find he was still alive and asked him, “Any chance

of you producing a few more sessions?” The nice

thing about having Seshi run a session is that he

knows the local music, and which performers will give

a good performance of a particular piece. He makes

sure that Bollywood pop music is banished during the

session. I think of him as my Bollywood filter.

That’s an increasing problem isn’t it?

It is. That’s why I like to work with somebody

knowledgeable within the culture. In remote villages

I always seek out local educated people,

administrators, school teachers, doctors and other

professionals, and enlist their help. They make really

helpful intermediaries with the local musicians, who

are generally farmers or laborers. They explain that I

want the pure local music - not Bollywood hits.

Sometimes young sprigs who like my lifestyle will

write me, asking questions. One thing they nearly

always overlook is budgeting adequate compensation

for the musicians. They write me saying “I plan to

make token payments to the musicians,” to which I

reply, “You don’t get it. The compensation needs to

be meaningful.” And they say, “Oh, but I’m a starving

student.” I tell them, “Look, if you go into a culture

where they barely have a pair of shoes and you have

all of this fancy gear…Let me give you an example:

If a well-to-do young Japanese guy were to come into

your college town, with a lot of fancy gear you know

you’ll never be able to afford, and say he’d like to

record your group, offering to pay you the sum you’d

normally make for a day’s work for recording an hour

of your music, you’d think that was fairly decent.

You’d think that was fair, wouldn’t you?” And the

young sprig replies, “Yes.” And then I’d tell them,

“Just think, how would you feel if he came in with all

this fancy gear, having paid for this expensive trip

from Japan, and then all he wanted to give you was

a ball point pen?”

What about publishing?

If I’m working with traditional music, I’m assuming it’s

public domain. What I’ve done is to write a one-

paragraph release, which covers the essentials. In

some situations, the payment for the performance may

not be a complete buyout, so there’s space on the

release form to write in how much more will come to

the musicians if the recording is used. That happened

when I was in Morocco in ‘98. There, $200 is a

ridiculously small sum to pay for a recording session,

but it was all I could afford. The musicians weren’t

happy, but I explained that I only had $1,000 to pay

all of the groups. So we agreed - 200 bucks down now,

and then if it’s released, they will get an additional

payment. Later, at the urging of a respected

entertainment lawyer, I decided to copyright all my

recordings. That way there will be some publishing

income to send back to the musicians.

When you are recording outdoors have

you ever had any really nasty traffic

noises or airplanes or stuff like that

get in the way?

That’s something that needs to be discussed with the

musicians. If you go in during the day and you’re

setting up an evening session, ask them, “Is it very

noisy here at night?” And they’ll say, “What do you

mean?” And then you can say, “Well how about

traffic? How about dogs? How about young kids,

because kids love to cluster around the mics. So you

need an agreement to banish the dogs and kids while

the recording is taking place.

Any unusual recording setups that

you’ve had?

In ‘87 I made three recordings of one particular kecak.*

First of all, the group wasn’t very good. And then the

places where I recorded were unsuitable, and the mic

placement didn’t help. It sounded uninteresting,

mediocre. Then I was referred to a better group in

Bona Village, which is the home of the kecak. We met

the kecak’s manager, agreed on the details and

recorded them in the very large, open courtyard of the

local Temple of the Dead, which is a traditional place

for kecak performances. My 200-foot hank of eighth-

inch nylon twine came in very handy. I ran it across

the temple, attaching the ends high up on pillars on

both sides. Then I hung the RE50s from the twine,

roughly 12 feet above the kecak performers,

separated by 20 to 30 feet. The result: A recording

that captured the drama of a fine performance. If

something doesn’t work, you have to scratch your

head and try again. In ‘66 I recorded gamelan with a

spaced pair of cardioids, letting the gamelan set up

the way it always does. When I went back in ‘87, I

tried the same thing and was dismayed with how

lousy the recording sounded. So after a few more

unsatisfactory recording sessions we tried something

different. The 20-piece ensemble, called gamelan

gong, consists of a large section of melody

metallophones, called gangsas**, each played with a

single mallet; a few gender —large two-mallet

metallophones; a wooden frame containing several

gong pots, called a reong; a single gong pot used as

a time beater; small cymbals, cheng-cheng; three

gongs, the largest more than a meter in diameter; two

drummers, and a flutist. In a large open space, we put

the RE50s spaced 15 to 20 feet. Visualize the

“recording space” as an inverted “V” with its

narrowest point at the back and the widest point

close to the mics. At the very back we put the three

gongs, centered. We put the gender andreong off to

36

/Tape Op#57/Mr. Lewiston/(Continued on page 38)