8

aligned, the object should be visible somewhere in the field

of view.

Once the object is visible in the telescope’s eyepiece, use

the slow-motion controls to center it in the field of view. You

can now switch to a higher magnification eyepiece, if you

wish. After switching eyepieces, you can use the slow-motion

control cables to re-center the image, if necessary.

The Dec. slow-motion control cable can move the telescope

a maximum of 25°. This is because the Dec. slow-motion

mechanism has a limited range of mechanical travel. (The

R.A. slow-motion mechanism has no limit to its amount of

travel.) If you can no longer rotate the Dec. control cable in

a desired direction, you have reached the end of travel, and

the slow-motion mechanism should be reset. This is done by

first rotating the control cable several turns in the opposite

direction from which it was originally being turned. Then,

manually slew the telescope closer to the object you wish

to observe (remember to first loosen the Dec. lock knob).

You should now be able to use the Dec. slow-motion control

cable again to fine adjust the telescope’s position.

Tracking Celestial Objects

When you observe a celestial object through the telescope,

you’ll see it drift slowly across the field of view. To keep it in

the field, if your equatorial mount is polar-aligned, just turn

the R.A. slow-motion control. The Dec. slow-motion control is

not needed for tracking. Objects will appear to move faster at

higher magnifications, because the field of view is narrower.

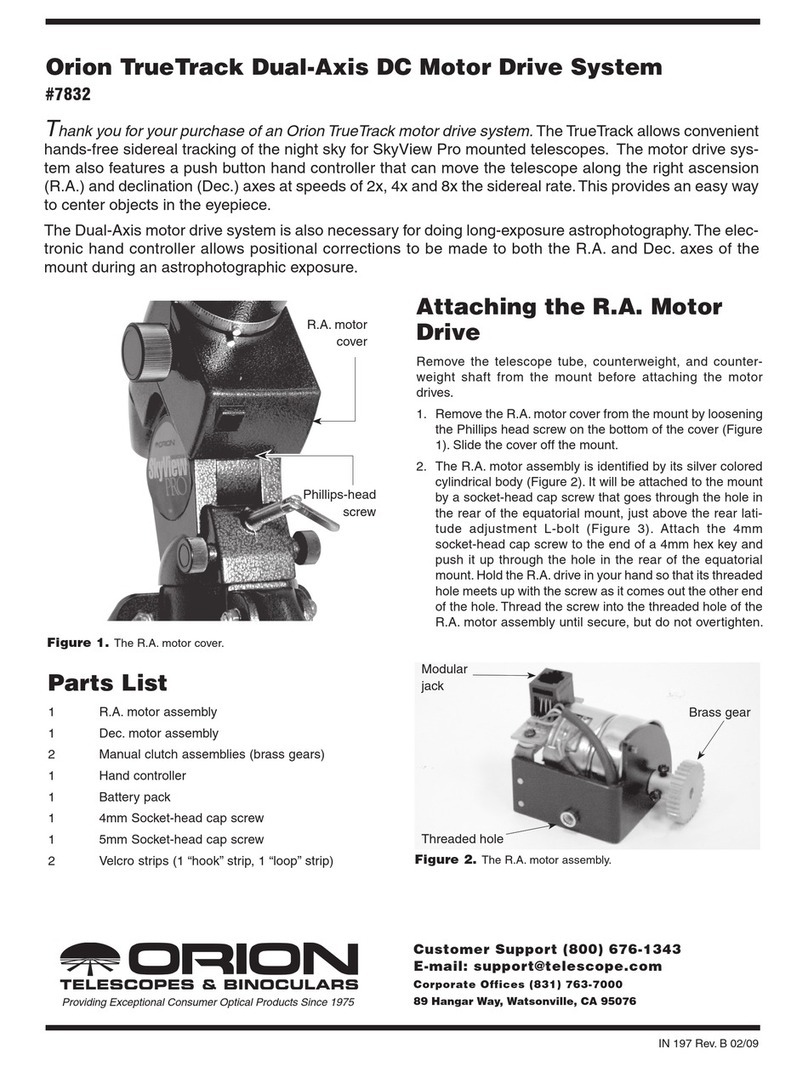

Optional Motor Drives for Automatic Tracking

and Astrophotography

An optional DC motor drive can be mounted on the R.A. axis

of the AstroView’s equatorial mount to provide hands-free

tracking. Objects will then remain stationary in the field of

view without any manual adjustment of the R.A. slow-motion

control.

Understanding the Setting Circles

The setting circles on an equatorial mount enable you to

locate celestial objects by their “celestial coordinates”. Every

object resides in a specific location on the “celestial sphere”.

That location is denoted by two numbers: its right ascension

(R.A.) and declination (Dec.). In the same way, every location

on Earth can be described by its longitude and latitude. R.A.

is similar to longitude on Earth, and Dec. is similar to latitude.

The R.A. and Dec. values for celestial objects can be found

in any star atlas or star catalog.

The R.A. setting circle is scaled in hours, from 1 through 24,

with small marks in between representing 10-minute incre-

ments (there are 60 minutes in 1 hour of R.A.). The lower

set of numbers (closest to the plastic R.A. gear cover) apply

to viewing in the Northern Hemisphere, while the numbers

above them apply to viewing in the Southern Hemisphere.

The Dec. setting circle is scaled in degrees, with each mark

representing 1° increments. Values of Dec. coordinates

range from +90° to -90°. The 0° mark indicates the celestial

equator. When the telescope is pointed north of the celestial

equator, values of the Dec. setting circle are positive, and

when the telescope is pointed south of the celestial equator,

values of the Dec. setting circle are negative.

So, the coordinates for the Orion Nebula listed in a star atlas

will look like this:

R.A. 5h 35.4m Dec. -5° 27'

That’s 5 hours and 35.4 minutes in right ascension, and -5

degrees and 27 arc-minutes in declination (there are 60 arc-

minutes in 1 degree of declination).

Before you can use the setting circles to locate objects, the

mount must be well polar aligned, and the R.A. setting circle

must be calibrated. The Dec. setting circle has been perma-

nently calibrated at the factory, and should read 90° when-

ever the telescope optical tube is parallel with the R.A. axis.

Calibrating the Right Ascension Setting Circle

1. Identify a bright star near the celestial equator (Dec. = 0°)

and look up its coordinates in a star atlas.

2. Loosen the R.A. and Dec. lock knobs on the equatorial

mount, so the telescope optical tube can move freely.

3. Point the telescope at the bright star near the celestial

equator whose coordinates you know. Lock the R.A. and

Dec. lock knobs. Center the star in the telescope’s field of

view with the slow-motion control cables.

4. Loosen the thumb screw located just above the R.A. set-

ting circle pointer; this will allow the setting circle to rotate

freely. Rotate the setting circle until the pointer indicates

the R.A. coordinate listed in the star atlas for the object.

Retighten the thumb screw.

Finding Objects With the Setting Circles

Now that both setting circles are calibrated, look up in a star

atlas the coordinates of an object you wish to view.

1. Loosen the Dec. lock knob and rotate the telescope until

the Dec. value from the star atlas matches the reading on

the Dec. setting circle. Remember that values of the Dec.

setting circle are positive when the telescope is pointing

north of the celestial equator (Dec. = 0°), and negative

when the telescope is pointing south of the celestial

equator. Retighten the lock knob.

2. Loosen the R.A. lock knob and rotate the telescope until

the R.A. value from the star atlas matches the reading

on the R.A. setting circle. Remember to use the lower set

of numbers on the R.A. setting circle. Retighten the lock

knob.

Most setting circles are not accurate enough to put an object

dead-center in the telescope’s eyepiece, but they should

place the object somewhere within the field of view of the

finder scope, assuming the equatorial mount is accurately

polar aligned. Use the slow-motion controls to center the

object in the finder scope, and it should appear in the tele-

scope’s field of view.