PicoQuant GmbH HydraHarp 400 Software V. .0.0.1

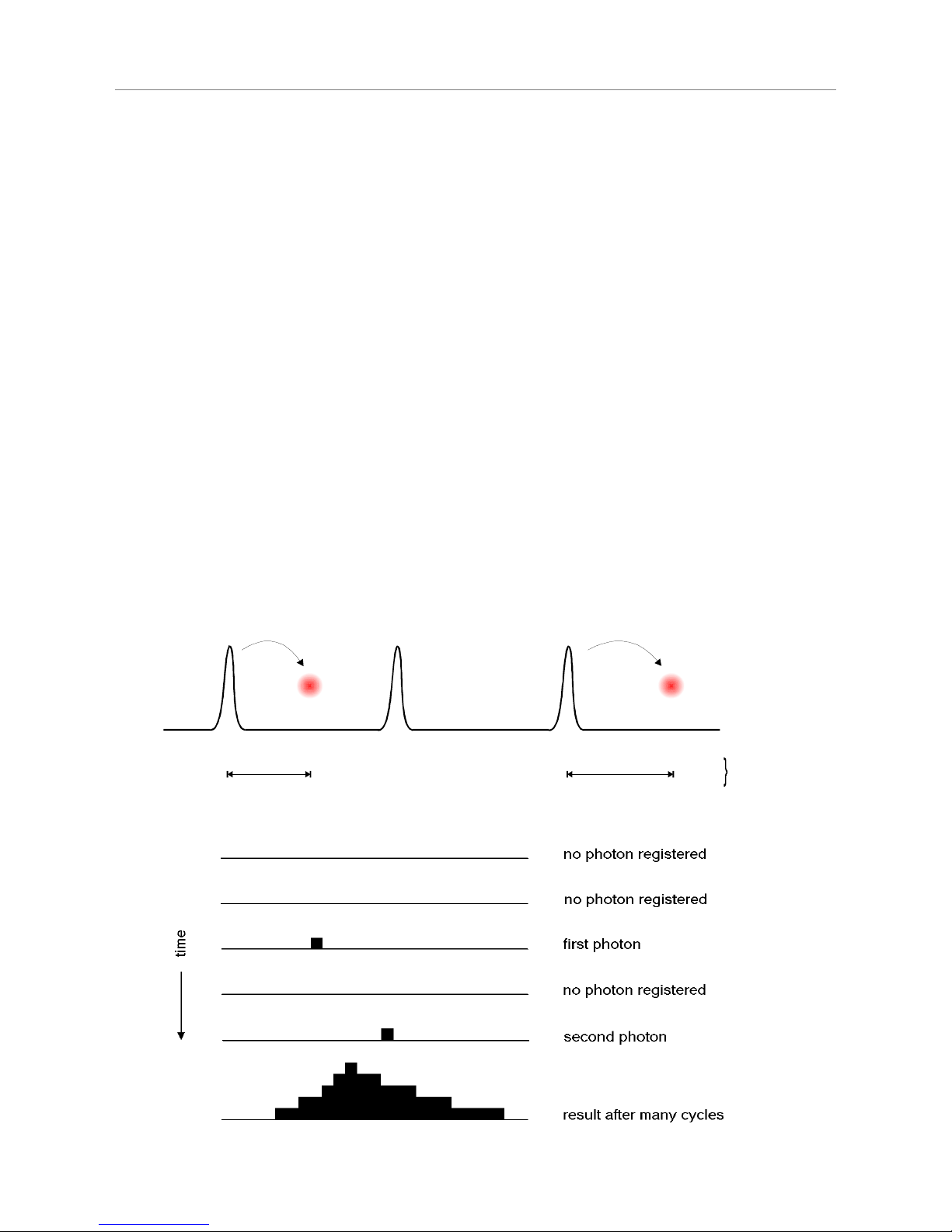

The histogram is collected in a block of memory, where one memory cell holds the photon counts for one

corresponding time bin. These time bins are often (historically) referred to as time channels. In practice, the

registration of one photon involves the following steps: first, the time difference between the photon event and

the corresponding excitation pulse must be measured. For this purpose both signals are converted to electrical

signals. For the fluorescence photon this is done via the single photon detector mentioned before. For the

excitation pulse it may be done via another detector if there is no electrical sync signal supplied by the laser.

Obviously, all conversion to electrical pulses must preserve the precise timing of the signals as accurately as

possible. The actual time difference measurement is done by means of fast electronics which provide a digital

timing result. This digital timing result is then used to address the histogram memory so that each possible

timing value corresponds to one memory cell or histogram channel. Finally the addressed histogram cell is

incremented. All steps are carried out by fast electronics so that the processing time required for each photon

event is as short as possible. When sufficient counts have been collected, the histogram memory can be read

out. The histogram data can then be used for display and e.g. fluorescence lifetime calculation. In the following

we will expand on the various steps involved in the method and associated issues of importance.

2.1. Count Rates and ingle Photon tatistics

It was already mentioned that it is necessary to maintain a low probability of registering more than one photon

per cycle. This was to guarantee that the histogram of photon arrivals represents the time decay one would

have obtained from a single shot time–resolved analog recording (The latter contains the information we are

looking for). The reason for this is briefly the following: Due to dead times of detector and electronics for at

least some tens of nanoseconds after a photon event, TCSPC systems are usually designed to register only

one photon per excitation / emission cycle. If now the number of photons occurring in one excitation cycle were

typically >1, the system would very often register the first photon but miss the following one or more. This

would lead to an over–representation of early photons in the histogram, an effect called ‘pile–up’. This leads to

distortions of the fluorescence decay, typically the fluorescence lifetime appearing shorter. It is therefore crucial

to keep the probability of cycles with more than one photon low.

To quantify this demand, one has to set acceptable error limits and apply some mathematical statistics. For

practical purposes one may use the following rule of thumb: In order to maintain single photon statistics, on

average only one in 20 to 100 excitation pulses should generate a count at the detector. In other words: the

average count rate at the detector should be at most 1 % to 5 % of the excitation rate. E.g. with the diode laser

PDL 800–B, pulsed at 80 MHz repetition rate, the average detector count rate should not exceed 4 Mcps. This

leads to another issue: the count rate the system (of both detector and electronics) can handle. Indeed 4 Mcps

may already be stretching the limits of some detectors and usually are beyond the capabilities of older TCSPC

systems. Nevertheless, one wants high count rates, in order to acquire fluorescence decay histograms quickly.

This may be of particular importance where dynamic lifetime changes or fast molecule transitions are to be

studied or where large numbers of lifetime samples must be collected (e.g. in 2D scanning configurations). This

is why high laser rates (such as 40 or 80 MHz from the PDL 800–B) are important. PMTs can safely handle

TCSPC count rates of up to 10 Mcps, standard (passively quenched) SPADs saturate at a few hundred kcps,

actively quenched SPADs may operate up to 5 Mcps but some types suffer resolution degradation when

operated too fast. Old NIM based TCSPC electronics can handle a maximum of 50 to 500 kcps, newer

integrated TCSPC boards may reach peak rates of 5 to 10 Mcps. With the HydraHarp 400, in each channel

average count rates of 6 Mcps and peak rates up to 12.5 Mcps can be collected. It is worth noting that the

photon arrival times are typically random so that there can be bursts of high count rate and periods of low count

rates. Bursts of photons may still exceed the average rate. This should be kept in mind when comparing count

rates considered here and elsewhere. The specifications for TCSPC systems may interpret their maximum

count rates differently in this respect. This is why another parameter, the so called dead–time is also of interest.

This quantity describes the time the system cannot register photons while it is processing a previous photon

event. The term is applicable both to detectors and electronics. Dead–time or insufficient throughput of the

electronics do not usually have a detrimental effect on the decay histogram or, more precisely, the lifetime to be

extracted from the latter, as long as single photon statistics are maintained. However, the photon losses

prolong the acquisition time or deteriorate the signal to noise ratio (SNR) if the acquisition time remains fixed. In

applications where the photon burst density must be evaluated (e.g. for molecule transition detection) dead–

times can be a problem. The HydraHarp 400 has an extremely short dead time of typically less than 80 ns,

imposing the smallest losses possible with instruments of comparable resolution today.

Page 7