6 | Clinical Practice Manual

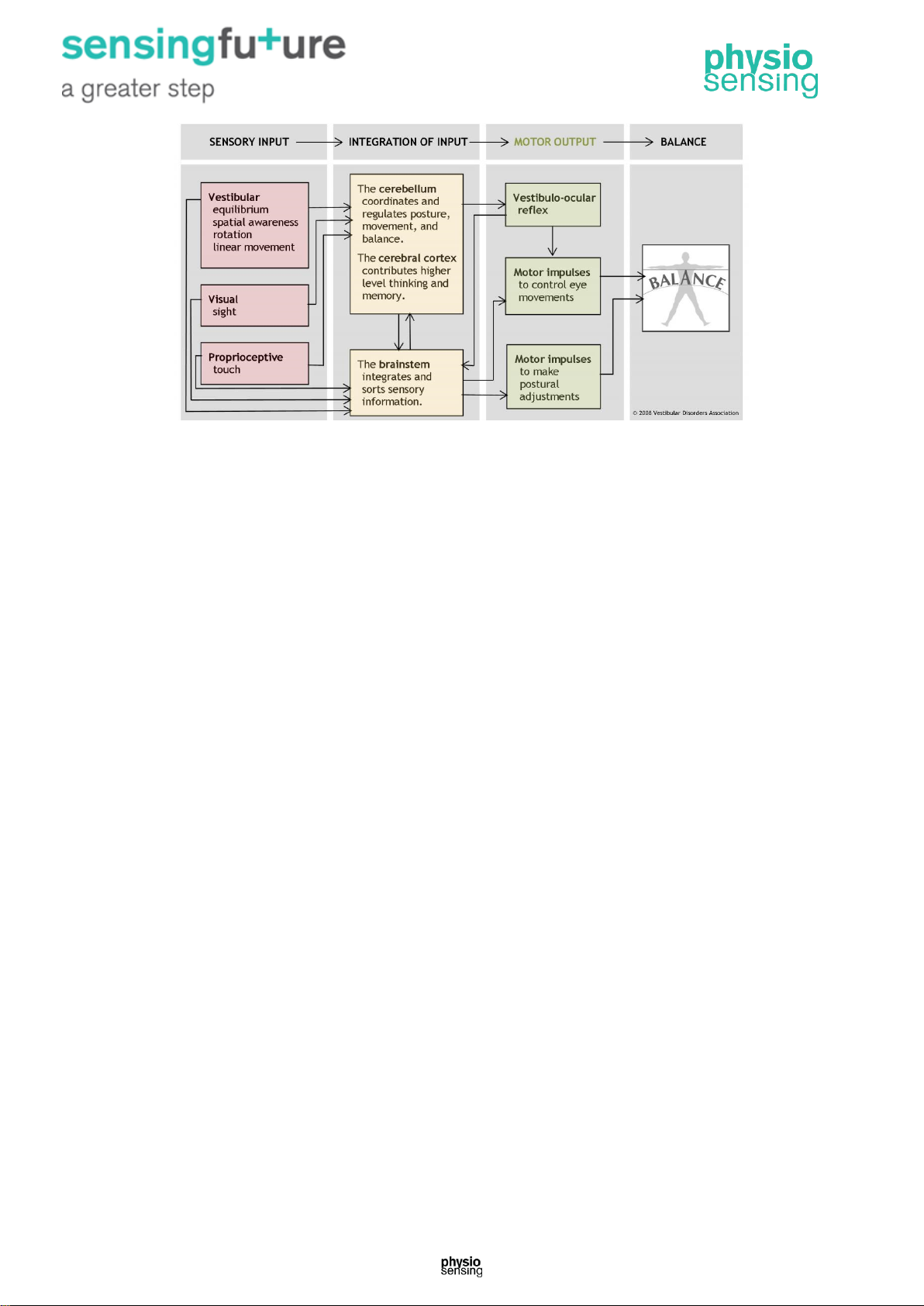

1.10. Motor output to the muscles and joints

A baby learns to balance through practice and repetition as impulses sent from the sensory

receptors to the brain stem and then out to the muscles form a new pathway. With repetition,

it becomes easier for these impulses to travel along that nerve pathway –a process called

facilitation –and the baby is able to maintain balance during any activity. Strong evidence

exists suggesting that such synaptic reorganization occurs throughout a person’s lifetime of

adjusting to changing motion environs.

This pathway facilitation is the reason dancers and athletes practice so arduously. Even very

complex movements become nearly automatic over a period of time. This also means that if

a problem with one sensory information input were to develop, the process of facilitation can

help the balance system reset and adapt to achieve a sense of balance again.

For example, when a person is turning cartwheels in a park, impulses transmitted from the

brain stem inform the cerebral cortex that this particular activity is appropriately

accompanied by the sight of the park whirling in circles. With more practice, the brain learns

to interpret a whirling visual field as normal during this type of body rotation. Alternatively,

dancers learn that in order to maintain balance while performing a series of pirouettes, they

must keep their eyes fixed on one spot in the distance as long as possible while rotating their

body.

1.11. Motor output to the eyes

The vestibular system sends motor control signals via the nervous system to the muscles of

the eyes with an automatic function called the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR). When the head

is not moving, the number of impulses from the vestibular organs on the right side is equal to

the number of impulses coming from the left side. When the head turns toward the right, the

number of impulses from the right ear increases and the number from the left ear decreases.

The difference in impulses sent from each side controls eye movements and stabilizes the

gaze during active head movements (e.g., while running or watching a hockey game) and

passive head movements (e.g., while sitting in a car that is accelerating or decelerating).

1.12. The coordinated balance system

The human balance system involves a complex set of sensorimotor-control systems. Its

interlacing feedback mechanisms can be disrupted by damage to one or more components

through injury, disease, or the aging process. Impaired balance can be accompanied by

other symptoms such as dizziness, vertigo, vision problems, nausea, fatigue, and

concentration difficulties.

The complexity of the human balance system creates challenges in diagnosing and treating

the underlying cause of imbalance. The crucial integration of information obtained through

the vestibular, visual, and proprioceptive systems means that disorders affecting an

individual system can markedly disrupt a person’s normal sense of balance. Vestibular

dysfunction as a cause of imbalance offers a particularly intricate challenge because of the

vestibular system’s interaction with cognitive functioning, and the degree of influence it has

on the control of eye movements and posture.