2.07. LINE/LOAD REGULATION - In the VOLTAGE FEEDBACK Mode, the Line Regulation of

the Unibond is 1% total for a t13% change in input line voltage. The Load Regulation

is 1% for an 800 amp change in output current. The response time is approximately

0.5 ms.

2.08. ACCURACY - The absolute accuracy of the PULSE AMPLITUDE Thumbwheel settings,

measured at the sensing point, is 13% of setting, 15 mv, in the VOLTAGE FEEDBACK

Mode. The output voltage for any given setting will repeat within 0.1%. The width

of the output pulse will be linear within 0.05 ms of the value set on the PULSE WIDTH

Thumbwheels.

2.09. VOLTAGE FEEDBACK MODE - In this mode, the Unibond will maintain constant

voltage, at the sensing point, as preset on the PULSE AMPLITUDE Thumbwheels. WHEN

THE UNIBOND II IS USED IN THE VOLTAGE FEEDBACK MODE ITS OUTPUT WILL BE IDENTICAL TO

THAT OF THE UNITEK UNIBOND I, Stock Numbers 01-124-01 through 05, AND OUTPUT

TRANSFORMER, Stock Numbers 9-001-01 or 10-105-01 through 04, OPERATED IN THE MANUAL

MODE.

2.10. VOLTAGE + CURRENT FEEDBACK MODE - In this mode, the Unibond will continuous-

ly increase the Pulse Amplitude to a maximum of twice, or reduce it to a minimum of

one-half, of the value preset on the Pulse Amplitude Thumbwheels in an effort to

maintain the output voltage-current product as indicated in Figure 24. This Mode is

designed to be effective for Weld Resistances between 1 and 15 milliohms. The re-

sistance connected between the Output Transformer Terminals and the Welding Load

should not exceed 1.5 milliohms. The resistance of the Models 40, 46, 86, 87, 127,

and 147 Weld Heads are 1.5 milliohms or less. The performance of the system will be

reduced as the resistance between the Terminals of the Output Transformer and the

Sensing Point is increased or if the Weld Resistance is less than 5 milliohms.

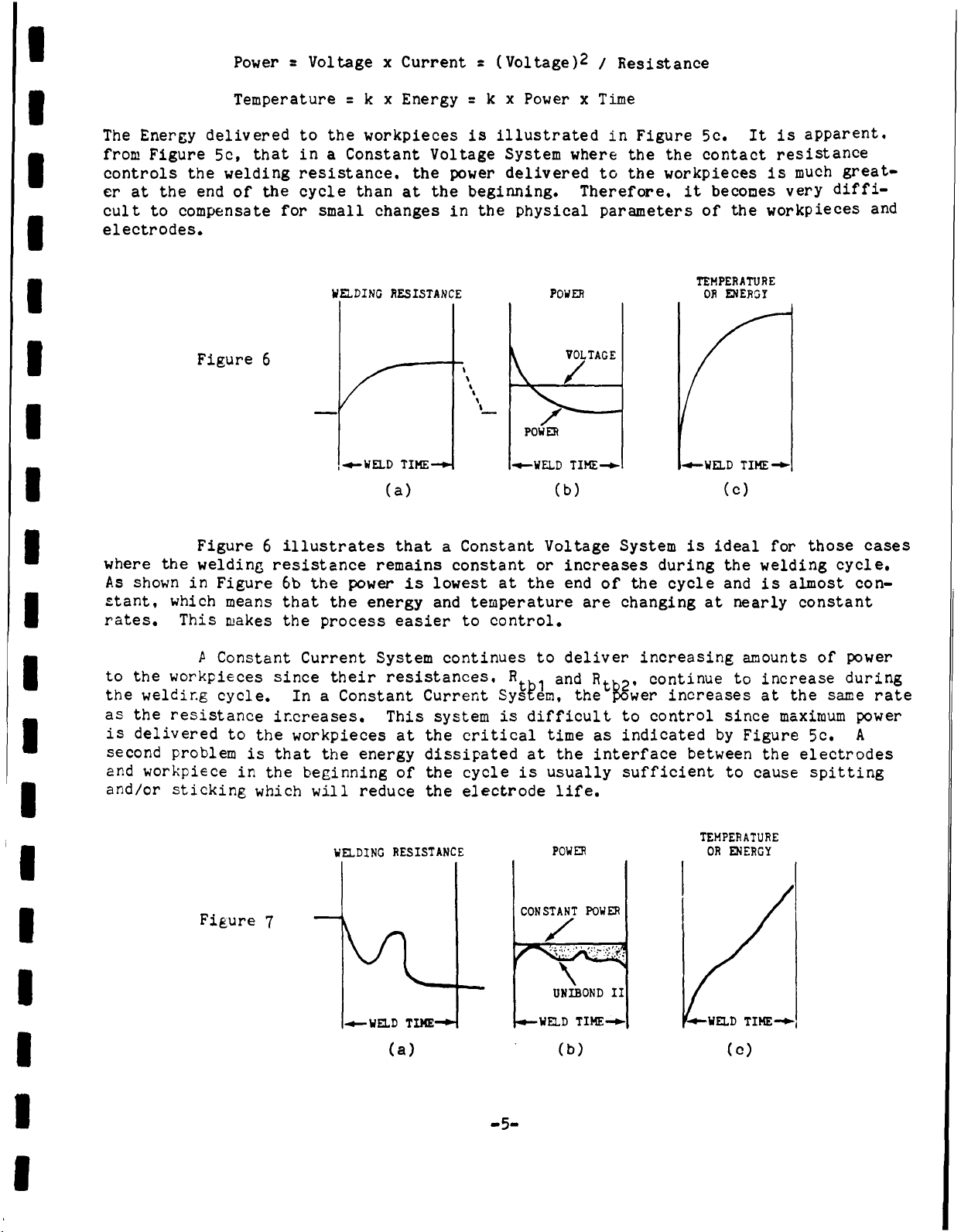

2.11. VOLTAGE + CURRENT FEEDBACK MODE - HOW IT WORKS - The welding process uses

both heat and pressure to form a weld. Electrode pressure is used to force the metals

together. Heat, generated by the resistance of the workpieces to the flow of elec-

tricity, either melts the material at the interface or at least reduces its strength

to a level where the surface becomes plastic. When the flow of current stops, the

electrode force is maintained for the fraction of a second required for the weld to

cool and solidify.

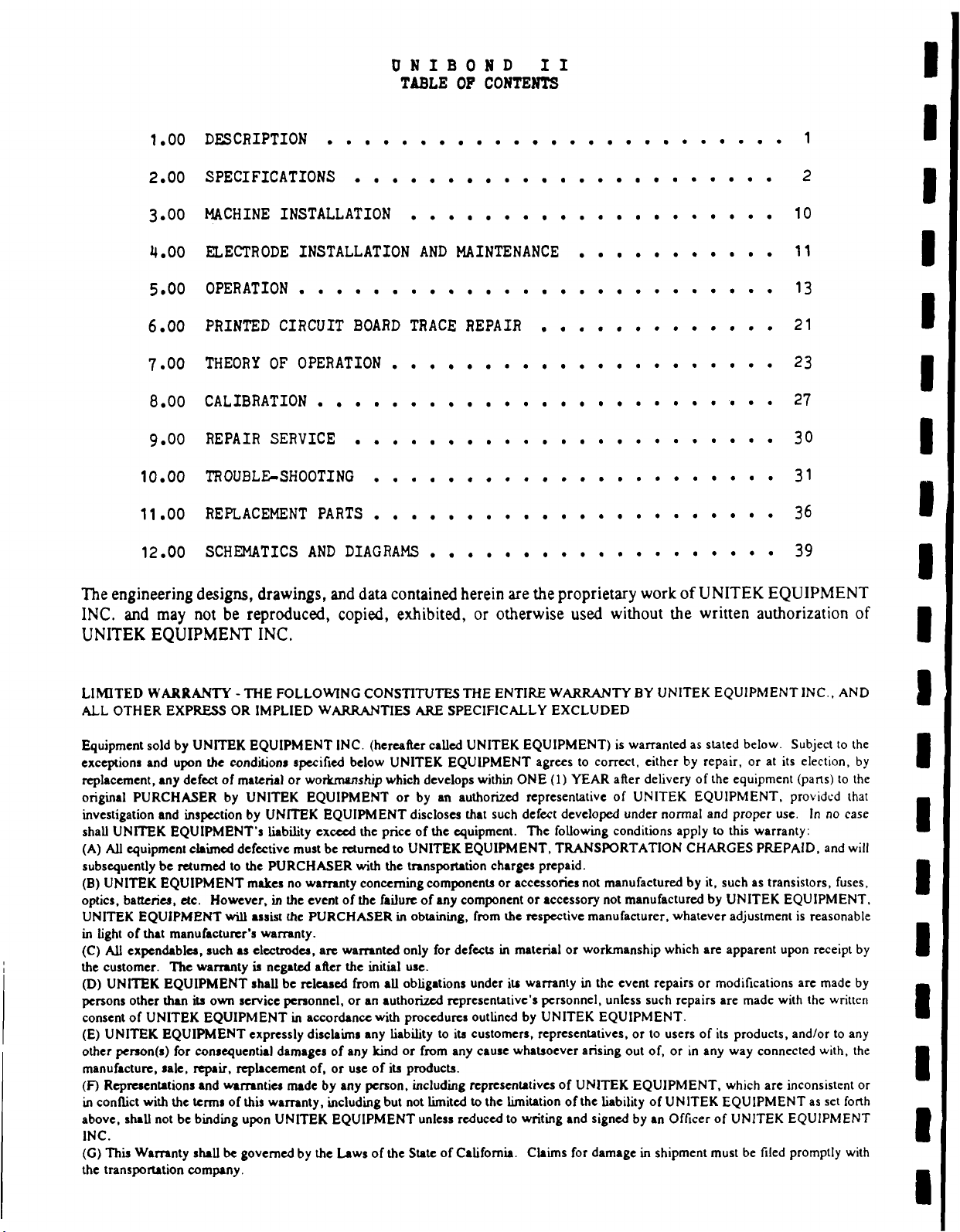

Figure 3 illustrates why the workpieces melt at their inter-

face. The surfaces of metal are quite rough if they are ex-

amined on a molecular scale. When the metals are forced

together with a relatively small force some of the peaks make

contact. On those peaks where the contact pressure is suffi-

ciently high the oxide layer breaks, forming a limited number

of metal-to-metal bridges. The weld current is distributed

over a large area as it passes through the bulk metal. As it

approaches the interface, the current is forced to flow

through these metallic bridges. This "necking down" increases

the current density, generating enough heat to cause melting.

As the first of these bridges melt and collapse, new peaks

come into contact, forming new bridges and additional current

paths. The resistance of the molten metal is higher than that

of the new bridges, so that the current flow transfers from

bridge-to-bridge. This process continues until the entire

interface is molten. When the current stops, the electrodes

rapidly cool the molten metal which solidifies,

forming a weld.

CURRENT

Figure 3