Brief History of Revolutionary War Gunboats

(courtesy Lake Champlain Maritime Museum)

The American Revolution was in its infancy when the Continental Congress gave orders “to build,

with all expedition, as many gallies and armed vessels as ... shall be sufcient to make us indisputably

masters of the lakes Champlain and George.” (Journal of the Continental Congress, June 17, 1776 in

Clark, Morgan, and Crawford, Naval Documents of the American Revolution, 5:589.) American leaders

were concerned about British forces to the north. All parties understood that control of the lakes

meant control of routes of attack and retreat; the corridor that included the Richelieu River, Lakes

Champlain and George, and the Hudson River was the most direct and easiest route between the

cities of Quebec and New York.

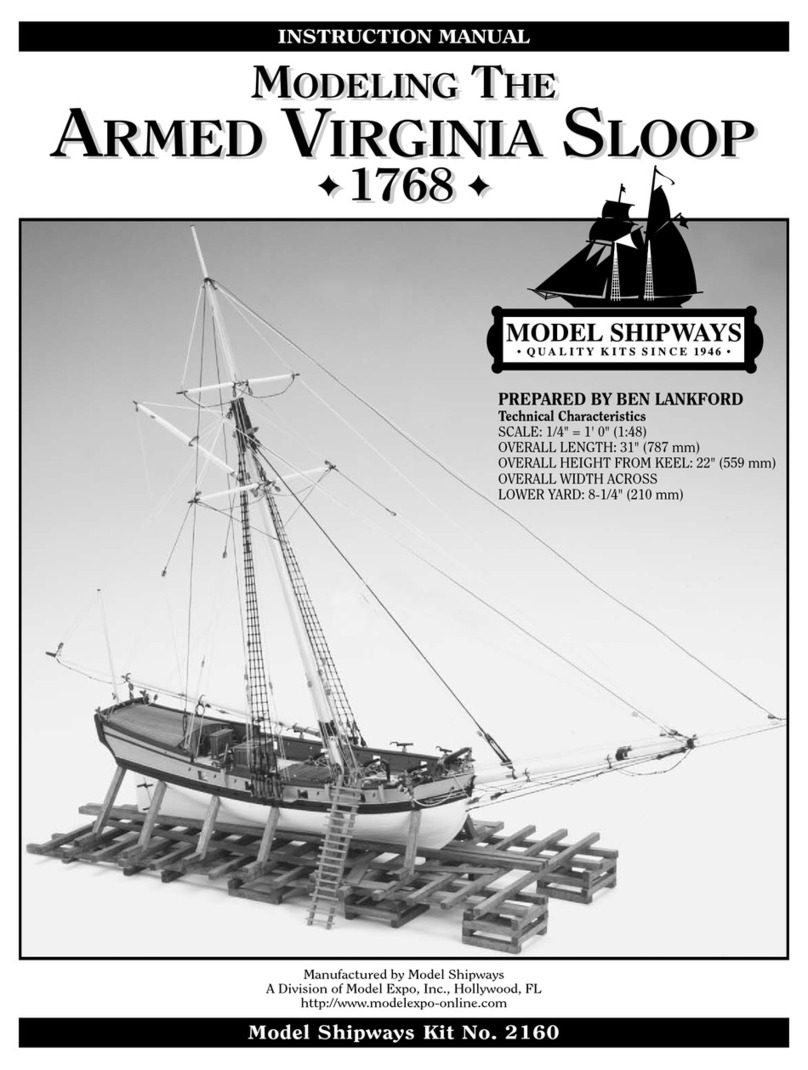

Control of the lake meant getting weapons onto the water as quickly as possibly. As a result,

Skenesborough (now Whitehall, NY) became the “Birthplace of the American Navy” in the summer

of 1776. General Philip Schuyler chose this location for its two sawmills and an iron forge, its ease

of defense, as well as access to the vast timber resources of the Adirondacks. The eet construction

itself was under the direction of Benedict Arnold, whose previous success as a merchant ship owner

and master made him the ideal candidate.

Construction began that summer at a slow pace. Carpenters, riggers were reluctant to leave their

lucrative businesses on the coast. Finally lured by higher wages, and despite the heat, mosquitoes,

black ies, and long days, these craftsmen completed eight 54-foot gondolas, including Philadelphia,

and four 72-foot galleys in just over two months.

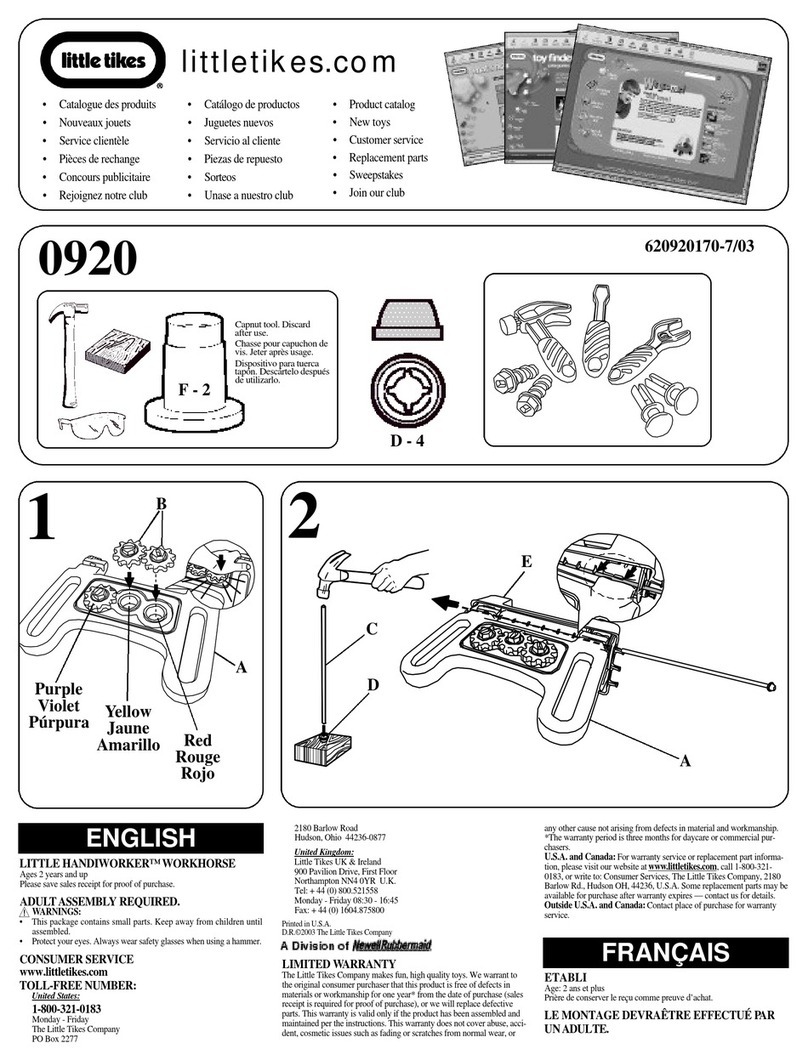

The gunboat was a at-bottomed rowing craft with square sails that enabled them to sail before

the wind. The hulls were tted out at Fort Ticonderoga. Across the lake at Mount Independence,

they were moored at the foot of a shoreside cliff; spars and guns were lowered from the top of the

cliff into position on board.

Philadelphia carried three carriage guns, one 12-pounder, and two 9-pounders, and eight swivel

guns. She had a single mast with a square-rigged mainsail and topsail. Her crew of 44 was captained

by 25-year-old Benjamin Rue, from Pennsylvania. With little experience in boat handling and none

in naval combat, Rue’s men typied the troops described to Major General Horatio Gates, as “a

wretched motley crew”.

This edgling eet spent the majority of their time that late summer and early fall of 1776 patrolling

the lake in anticipation of the completion of the British eet in Canada. Finally, on October 11,

1776, the British were carried southwards on a north wind. Arnold’s eet was moored in a protected

bay between Valcour Island and the New York shore in anticipation. The British did not enter the

Valcour Island passage from the north, but instead ran south to the east of Valcour Island, which

meant that to engage the Americans, the British would have to sail into the wind, putting them at

a disadvantage.

Despite this initial advantage, the British eet was much more powerful than the Americans. At

the end of the 6-hour battle, the schooner Royal Savage had been captured and burned, and the

gunboat Philadelphia sunk. Other vessels sustained damage, and sixty men were killed or wounded.

The British decided to wait until morning to nish off this rebel eet, which proved to be a poor

decision. During the night, the cunning Benedict Arnold led his eet in an escape, rowing silently