Perhaps it has been the lack of skilled engineers, maybe audiophiles at large have lacked discipline; for whatever reason the current

consumer playback world is lost in its conception of acoustics and the nature of sound—much has been written in consumer magazines

but little of it is genuine. Original recommended works on the subject include: Music, Physics and Engineering (formerly titled Musical

Engineering) by Harry F. Olson, Science & Music by Sir James Jeans, Fundamentals Of Musical Acoustics by Arthur H. Benade,

Fundamentals Of Acoustics by Lawrence E. Kinsler, Austin R. Frey, Alan B. Coppens and James V. Sanders. There are several other good

sources of researched data; these represent a good cross-section.

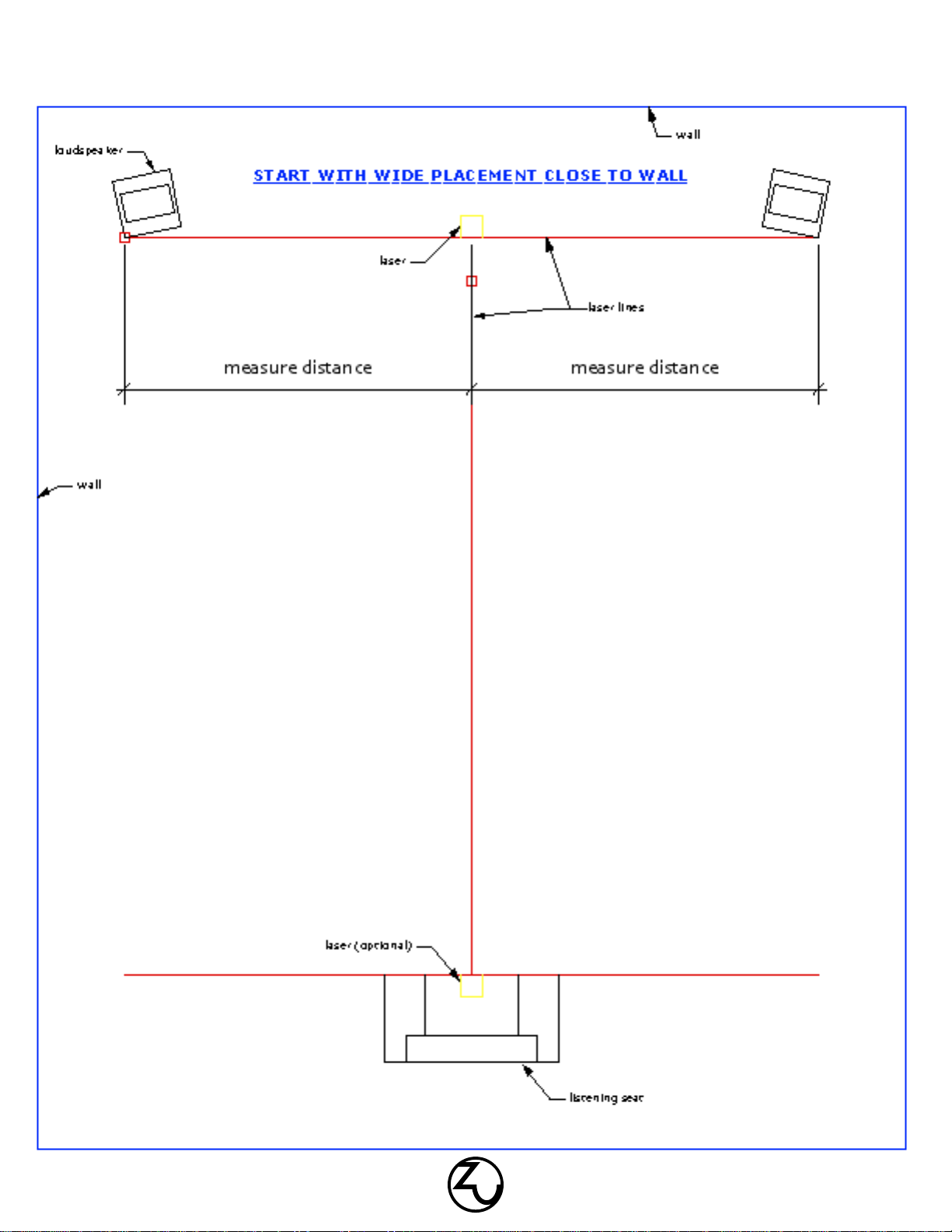

The following technique is Druid specific. It addresses the loudspeaker’s relationship with the room and works for both 2-channel and

multi-channel setups. How and where the loudspeakers excite the room and how the room reacts is relative to the type and source

of excitation and room reactance—a function of boundaries (walls, floors, etc.), boundary properties (mass, compliance, Q, damping,

texture and structure), area impedances (shape, volume), diffusion and absorption (furnishings, people, flooring, etc.), source and type

of wave excitation (loudspeaker design and placement), resonators (closets, forced air ducts, hallways, etc.), even atmospheric pressure

and humidity, though minor, will influence sound. While the above are beyond the scope of this guidebook, the recommendations and

listed books will start you down the proper acoustic path. Again, before you trust another modern work relative to playback and acoustics

please research the above listed references!

With your loudspeakers positioned for visual appeal, livability and fidelity, you can now begin fine-tuning. This involves three major steps.

In sequence they are bass, mids and treble. If you can’t fine-tune your system within an evening please contact us.

Base: Usually, you will have one loudspeaker that is framed with more wall space, this is the loudspeaker you will fine-tune and then

simply mirror the other. Select recordings with large amounts of sustained low frequency information; dramatic pipe organ and dance

music work as do test recordings that have warbled low frequency tracks (50 - 100 Hz range). Note that steady state sine, triangle and

square wave signal prove very difficult to interpret. Bass information with some transient content will enable the listener to make fast

work of fine-tuning. So here we go, with the loudspeaker playing at a moderate level, (only the “tuning loudspeaker” should be on)

walk over and kneel down next to it. Kneeling will put your head in the seated listening horizontal plane and allow you to hear how the

loudspeaker integrates with the room. Now move your head to either side of, and back and forth of the loudspeaker, say a half-meter (a

foot or so) in each axis. Listen to the fidelity of the bass, does it sound woolly and muddy right behind the loudspeaker? Is the bass more

defined a bit to the left or right? If the bass sounds better a bit to the left, move the loudspeaker to this position and then listen again.

Remember that moving the sound source also changes how the room reacts. You should only have to move the loudspeaker three or four

times to get the bass dialed in.

Midrange and treble: Once the lower octaves are sounding good, natural, vibrant midrange and treble can now be dialed in. Before you

begin I think it’s important to understand a few details. Midrange tuning, while similar to that of bass, is a task of a inches (decimeters)

rather than feet (half meters) and upper octaves a mater of fractions of an inches (centimeters / millimeters) and loudspeaker firing axis.

Even though midrange and treble changes can be heard at the being positioned loudspeaker, it is helpful to have a friend position while

you listen in the seating area. Here, you may want to select less bass heavy recordings; jazz, space-ambient, violin solos, guitar solos,

stuff with good overtone color and not too heavy.

Staying with the same loudspeaker “room-tuned” for low frequencies, (remember you only tune one channel and mirror its mate) and

with your favorite less heavy recording playing, start tuning for mids and highs. Move it toward the closest wall, in increments of a few

inches (4 - 6cm). While moving, the “sweet spot” listener, and possibly the person positioning the loudspeaker, should notice midrange

color transition from low-presence and masked to open and intimate. There may be several spots within the good sounding bass area

that have good presence, go with the widest point (closest to the wall) for an expansive and engaging soundstage. Don’t worry about

center focus, the Druid will knock your socks off with its capacity for expansive and focused soundstage recreation. Once a midrange

position is selected its time to work on the highest octave. This is usually as simple as rotating the Druid loudspeaker to face directly at,

or just behind, the seated listener. Now listen again for voice openness and intimacy, minor placement adjustments and loudspeaker face

angle may be necessary.

Additional thoughts about playback, room, and tonality

The attack, more than any other aspect of a waveform, gives the listener the clues to process source, direction, amplitude, character,

intelligence, and so on. Close in importance are the dynamics within that immediately follow the attack. A simple example: When a piano

key is struck, three main components are set in motion. These make up the attack of a note; the mechanical noises including that of

the impinging hammer, initial string motion, which has many extra components and initial coupling of piano body and sound board. The

first few milliseconds are very dynamic and have many features. To get the attack correct is solely a function of the playback system and

has very little to do with the room. Aside from placement, if you have changed your system to combat your room, attack and dynamics

can never be correct. Most people can only pinpoint tonal problems with steady-state or semi steady-state music or signal, this is a big

problem because room influence on steady-state sounds are huge, usually the single largest influence. Not realizing this, people usually

tweak things to get the steady-state and decay tonally correct which inadvertently kills the life in the attack. This is a reason why cables

as tone control, digital room correction, parametric equalizers and the like can never fix fundamental problems, unless of course the time

axis is also programmed and correlated to harmonic structure and then set to react to any dynamic anomalies within the signal—we’re a

few decades out on that I think.