On to the Capacitors – there are three types of

various values in the bag. Capacitors (or caps)

store electrical energy and are measured in

fractions of Farads – our typical values are in

picofarads (pF), nanofarads (nF) and microfarads

(

µ

f or uf) - 1000pF equals 1nF and 1000nF equals

1uf. We have two types of low value caps here –

the blue dipped-ceramic and the yellow polyester-

box type (these types are pretty similar for our

purposes) – note that these types are both non-

polarized. There are also the black cylindrical electrolytic caps. These ones are polarized

and must be used the correct way around – they have a positive side (the straight line on the

schematic symbol and the long leg on the actual cap) and a negative side (the short leg on

the cap – also there is a white stripe on this side with a minus symbol). We'll discuss more

about the use of these capacitors when we look at the circuitry in the next section.

The next parts to consider are the chips or Integrated Circuits (ICs). These come in a little

piece of foam along with IC holders for them – ICs can be sensitive (to heat or static

electricity) so we generally attach a holder to the PCB first and only add the ICs once the

circuit is complete (this also allows easy replacement if something breaks). There are literally

thousands of different types of ICs available today and within the fairly nondescript black

packages they actually contain miniature

electronic circuits (composed of parts like

resistors, capacitors, transistors etc). ICs have a

number of pins (or legs) – typically 8 or 14 in our

types of circuit – and these must be connected the

right way around for correct operation (indeed, a

chip will likely be killed if connected the wrong way

around!). Examining an IC you will notice a notch

at one end (or sometimes just a dot) – the pin to

the left of this is Pin1 and the numbering from here

goes down that side and then up the other. It is

beyond our scope to look into the vast variety of

chip functions available, but let's look at one type

that we're using and see how the package and

schematics hook up.

The two 14pin ICs we have are actually quite

similar to one another – they are both members of

the 4000 series CMOS Digital Family. One of the

best ways to find out information about an IC is to

go to Google and search for the datasheet. We'll

look at the 4069 so you could search for '4069

Datasheet'. We see that this chip is called a Hex Inverter – hex means it contains six

sections (gates) and the sections function as Inverters. Looking at the Pin Connection

diagram you can see how the six sections connect to the pins of the chip. Two pins are left

over and these are the power pins – pin7 is labeled Vss and this connects to Gnd, while

pin14 is called Vdd and will connect to V+. The scheme of having the Gnd pin at bottom right

and V+ pin at top left is actually universal throughout the 4000series CMOS family. Also note

that the Pin Connection for the 40106 happens to be very similar to the 4069 – it is a Hex

Schmitt Inverter and also has 6 sections connected in the same way, but the sections

provide slightly different functions from the 4069.

The next bag contains the dials or Potentiometers

(Pots). These are parts we use to control the

behaviour of the circuit. While the ones we're using

are small, they're pretty much the same as big dials

on HiFi systems or synths. Pots are variable

resistive elements with three pins and we'll use

them in one of two ways. The first way (shown on

the right) is called a Potential Divider (you can

check Wikipedia for a more detailed explanation).

There is a fixed value resistance between the outer

pins (1 and 3) and then a wiper that moves

between them as you move the dial. The way shown is used to attenuate a signal – ie as a

volume control – turned one way the full signal is passed while turning the other way will

make no signal pass. The second application involves tying two of the pins together to give

a variable resistor, a useful means of controlling the behaviour of a circuit – more details on

this in the circuitry section.

The last bag contains the final parts including the

switches which allow us to select different behaviours.

Mechanical switches are common in day to day life so

should require little introduction. These particular ones

have three terminals (the other legs are just for adding

stability) – when the switch is pushed one way then pins

1 & 2 are connected together, while the other way

connects pins 2 & 3, thus allowing us to select different routes within the circuitry.

There's not much left to examine – the Speaker should be

self-explanatory but lets just look at the Jack Socket. This is

a switched mono 1/4” socket (ie for standard guitar cable). It

has four legs, two on each side. The signal goes out on to

the tip of the jack plug and the sleeve connects to the circuit

Gnd. Note also that when no jack plug is inserted the legs on

either side are connected – this allows us to automatically

switch off the mini-speaker when a cable is plugged in.

When the plug is inserted the horizontal pieces of metal are

lifted up and thus the legs on the lower side are left unconnected.

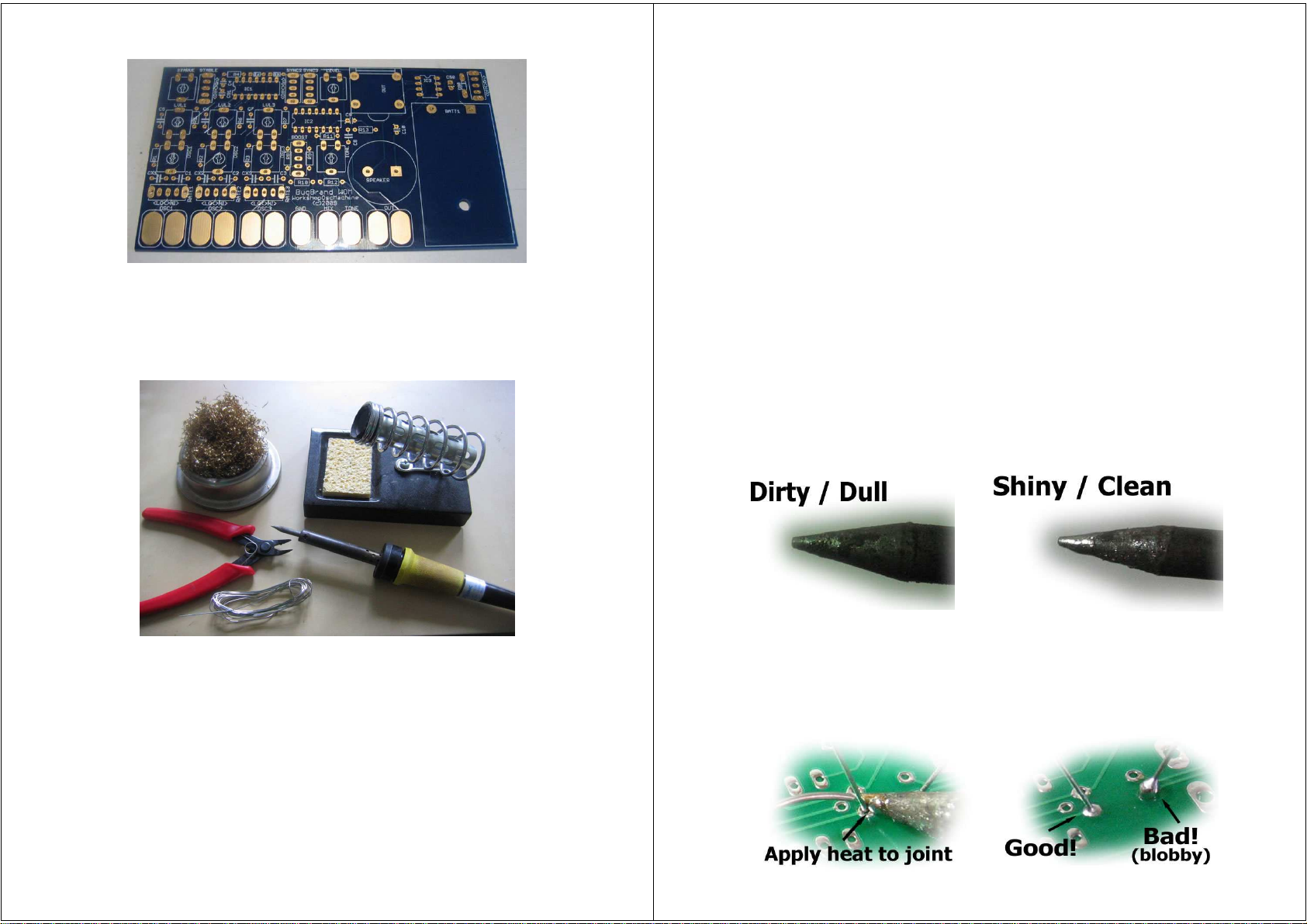

Finally lets take a quick look at the Printed Circuit Board (PCB). This has been specifically

designed for this project – laid out directly from the schematic diagram and fabricated in a

far-away land! Its actually quite a complex procedure to do such a design and for most one-

off circuits you'd simply use a material called stripboard (look it up) but for replicatable

projects it really makes sense – everything is laid out nicely and building errors are

minimized. If you examine the PCB you'll see tracks on the top and bottom of the board

joining the different parts together. The gold coloured pads for the components make

soldering easy (hopefully!). Now, people have asked why we make this project directly on the

PCB without using a box. I've found that these on-board-circuits are strong and reliable. The

time saved by avoiding putting it in a box is quite considerable and it also makes the project

a good deal less complicated. Over the years I've been building things I've found that the

most time consuming part of making devices is the boxing – wiring up pots and other

controls. The wiring is also a place were faults can easily develop and my aim for this project

has really been to make something that is almost guaranteed to work first time – the one

thing that kills a buzz for electronics really quickly is when you finish building something and

then it doesn't work!