Page 10

•Launch

The most important thing during the take-off is, like at all other gliders too, not the

force but the constancy of the pull. At the start we advice to fix the accelerator

with the Velcro which is attached at the front of the sitting board, in order to avoid

tripping while pulling up the glider or when starting up.

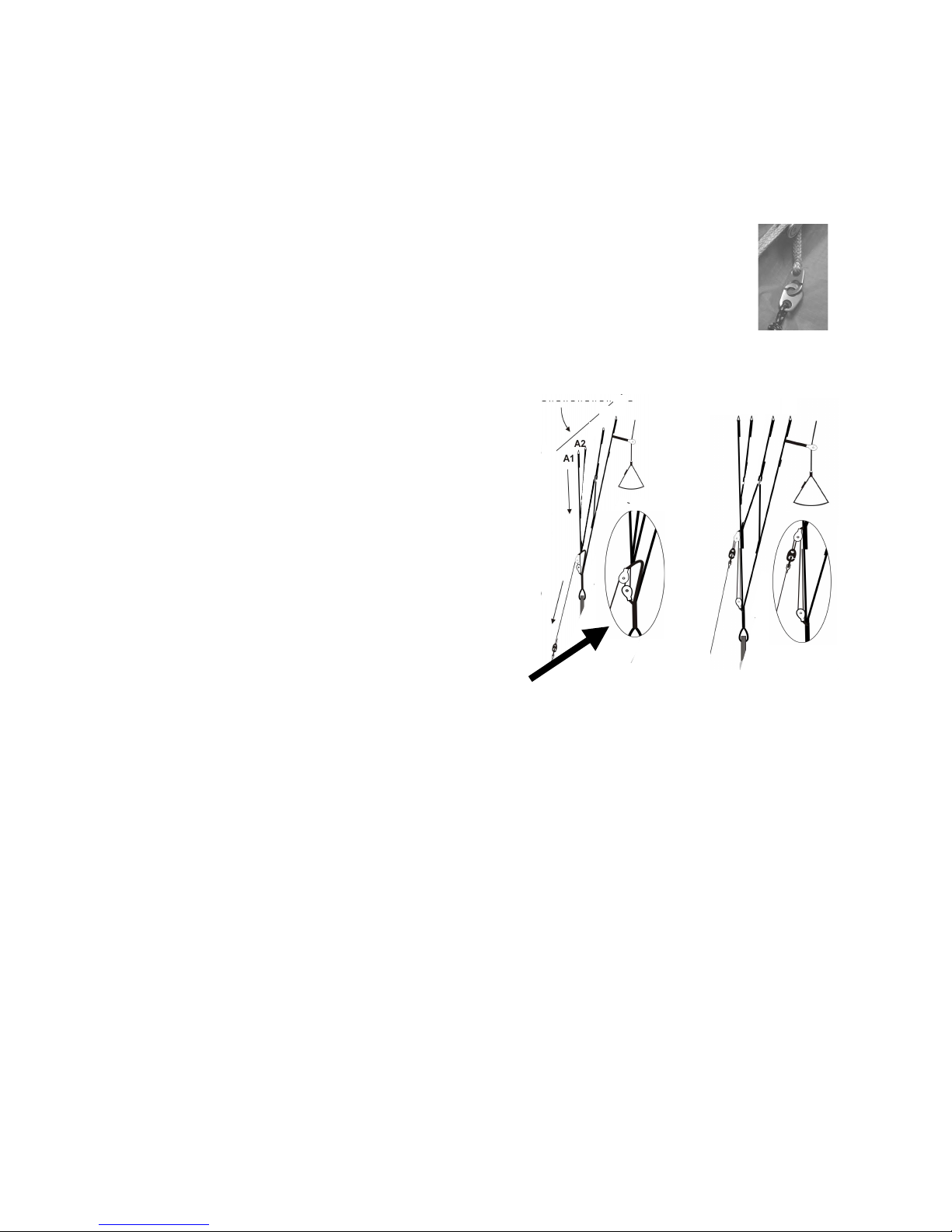

Hold the inner A-risers and the handles of the brakes and use progressive

pressure on the A-risers and the energy of your own body weight until the wing is

fully inflated overhead. The canopy is inflated quickly.

When there is no pull from the lines use slight pressure on the brake. After a few

accelerating steps and at the same time let go of the brakes gently, you will take

off. Then use slight pressure again on the brakes to fly at a speed with minimal

sink rate.

When there is strong wind the reverse launch technique is recommended. Holding

the brakes, turn around to face the wing passing one set of risers over your head

as you turn. We suggest building a "wall" by partially inflating your glider on the

ground, thus sorting out the lines thoroughly.

Check the airspace is clear and gently pull the glider up with inner riser. When the

glider is overhead, check it gently with the brakes, turn and launch. In stronger

winds, be prepared to take a couple of steps towards the glider as it inflates and

rises.

Active flying

Active flying in normal flight means that the wing is always kept at a safe angle of

attack and, if at all possible, vertically above the pilot. The moving air affecting the

wing often changes the angle of attack in an unwanted way. When flying into an

upwind the paraglider often bucks, the wing drops back, the angle of attack

increases, getting closer to a stall. In upwind the canopy pitches forward, the angle

of attack is reduced an there is the risk of a collapse. Both can occur

symmetrically, on both sides or asymmetrically, on one side only.

It is impossible to control the angle of attack by looking to the canopy. Look in the

direction you are flying, changes in the horizon inform the pilot about the canopy’s

movements.

Breaking is also an absolute must! If the canopy pitches forward, the angle of

attack decreases. In the case of strong forward pitching there is a risk of the

canopy collapsing due to its insufficient angle of attack. The pilot must therefore

prevent the canopy from pitching forward by pulling the controls down on both

sides. Inversely, the angle of attack increases if the wing drops back behind the

pilot, e.g. when entering into a thermal. The canopy is closer to stalling.

In these flight situations a significant breaking movement by the pilot can lead to a

spin or a stall. When the wing drops back, the pilot therefore must not break and/or

if the pilot is already holding the controls low, he must release them accordingly.

Any change in the angle of attack immediately transfers in to a change in the

control pressure of the brakes. The control pressure presents the pilot with

immediate information on the angle of attack and on what the canopy is doing or

about to do.