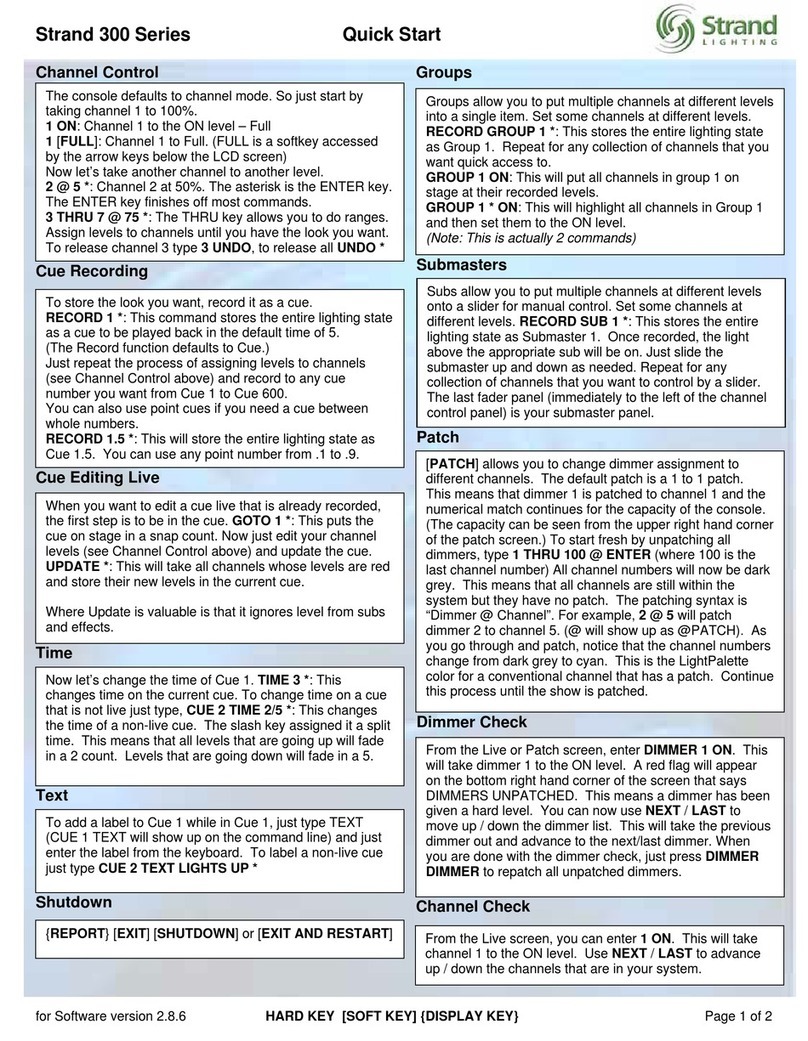

Strand Lighting ClassicPalette User manual

p1

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

Table of Contents

Concepts and Overview

6

Feature Overview

6

About Palette

10

System Capacities

12

Universal Attribute Control Model

14

Definition

15

Conclusion

38

Tracking

39

A Note on Redundant Data

41

Timing

43

Multiple Cue List Concept

48

Fade Resolution

50

HTP vs LTP

51

Priorities

53

Tips and Tricks

54

Screen Layout

60

Toolbars

60

Channel Grid

63

Channel's different states

65

Attribute Grid

68

File Menu

70

Display Menu

72

Help Menu

74

Softkeys

77

Status Window

80

Look Pages

83

Macro Buttons

86

View Properties

88

Remote Video

89

Screen Layout

91

Console Buttons

93

Display Keys

94

Live Button

94

Blind Button

95

Patch Button

96

Playback Keys

97

DBO Button

97

Go Button

98

Goto Cue Button

99

Select Button

100

Halt Back Button

101

Step Cue Buttons

102

Release Playback Button

103

Recording Keys

104

Record Button

104

Update Button

105

Cue Button

106

p2

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

Group Button

107

Look Button

108

Action Keys

109

Arrow Buttons

109

Delete Button

110

Edit Button

111

Load Button

112

Move / Copy Button

113

Tools Button

114

View Button

115

Main Keys

116

Additional 10-Key buttons

116

Next Button

117

Number Buttons

118

Release Button

119

Rem-Dim Button

120

Shift Button

121

Soft Keys

122

Up Button

123

Programming and Viewing Fixtures

124

Fixture Colors and Symbols

124

Command Line Syntax

128

Fixture Title

135

Captured Attributes

136

Selecting and Setting Channels

137

Using the Mouse to Select Channels and Set Levels

140

Controlling Moving Lights

142

Controlling Colour

149

Independent Timing

151

Effects

157

Release

164

Select Softkeys

166

Recording and Editing Cues

169

Recording Cues

169

Record Options

174

Updating Cues

179

Load

183

Blind

187

Edits Track Forward

190

Track Sheets

191

Move In Black

193

Cue Lists

196

Cue List Directory

196

Cue List

198

Cue List Properties

201

Cue List Pointer

204

Autoscroll Cue List

205

Blue Box

206

Profiles

211

Releasing & Asserting Cue Lists

217

p3

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

Step Forward and Back

218

Cue Numbering Scheme

219

Renumber Cues

220

Blocking and Unblocking of cues

222

Cue Properties

225

Deleting Cues

228

Goto Cue

230

Follow Cues

232

Linking Cues

234

Playback Loops

236

Action on GO within Cue Loop

238

Part Cues

240

SMPTE Timecode on Cue Lists

243

Recording and Using Looks and Groups

247

Looks

247

Sub Master Types

250

Recording Looks

252

Busking

256

Recording and Using Groups

258

Apply Levels/Palettes

259

Patching

261

Patch

261

Patch By Channel/Fixture

263

Patch By Output

267

Patch Routing

269

Capturing Outputs

272

Scrollers

273

Individual Attributes

275

Tools

277

Tools

277

SMPTE Learn Mode

279

Flip

280

Fanning

281

Highlight/Lowlight

284

Rem Dim

285

Colour Picker

286

Channel Check

288

Flash Fixture or Output

290

General Information

291

General Show Options

291

Default Cue List Options

293

Venue Setup/Location

296

Show Save Options

298

Move/Copy

301

ShowNet

307

Pathport

310

One to One Patch

312

Power Patch

313

Printing

315

Hardware Setup

317

p4

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

Hardware Setup Dialog Box

317

Priorities

318

A/B C/D

319

Grand Master and Black Out Button

323

Button Array

326

Button Array Described

328

Triggers

332

Trigger Wiring

333

Console

334

MIDI / SMPTE Interface

337

Remote Focus Unit

338

Macros & Show Control

340

Macro Editor & Commands

340

Macro Editor & Scripts

343

User Interface Macros

349

Variables, Button Stations & MIDI Notes

351

Vision Net

354

Time Events

358

Browser Control

363

Media Player Control

367

PowerPoint Automation

368

Serial Out Macros

371

Telnet and Serial Communications

373

MIDI Show Control

374

Palette Control Panel

376

Palette Control Panel

376

Upgrading Palette Software

378

Console Group

379

Launch Palette Button

379

Hardware Test

380

Release Notes

382

System Group

384

Date Time & Input Language

384

Screen Resolution

389

ELO Touch Screens

397

On-Screen Keyboard

399

Mouse

400

Keyboard

403

Accessibility

404

Network

405

MonitorPower

410

Network Printers

412

Shutdown

414

Applications Group

415

Explorer

415

MediaPlayer

417

Internet Explorer

420

Outlook Express

421

Notepad

422

Paint

423

p5

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

Additional Applications

424

System Up Time

425

Backup, Support and Contact Information

426

Tracking Backup

426

Recovery & Enable Outputs

428

Recalibrating, Striking and Dousing Fixtures

430

Software Revision History

431

Console Connections

433

Palette

433

Light Palette

436

Rack Palette

439

Appendix

442

License

442

Offices and Service Centres

444

Keyboard Shortcuts

445

p6

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

Concepts and Overview

Welcome Page

Date:

August 2008

Engine

Version:

v10.4.1

User Interface

Version:

v10.4.1

Congratulations on the purchase of your Strand Lighting Palette Lighting Control Console.

For general help, use the Contents, Index or Search tab on the left.

Check out the Software Revision History.

Palette is a powerful, yet easy to program and operate theatrical control system that truly does

marry dimming and automated control like no other desk. The key is in the software design,

using a Graphical User Interface, together with a control surface that gives you all the direct

access that you have come to expect from a professional lighting console. The core fade engine

works on the Last-Action philosophy, meaning levels and attributes stay put until another control

moves them, freeing you from recording all channels in all cues. This lends itself nicely to the

multiple cue list environment that Palette also boasts. Below are links to full-fledged help topics

that describe some of the keys features that make Palette a very powerful desk:

oUniversal Attribute Control Model - Horizon Control's UAC is a whole new way of

thinking about controlling moving lights. It frees the designer from the crazy world of

DMX charts and lets you think of the lights in your rig as tools to aid you in your

design.

oAdding Effects with Palette is as easy and convenient as making a gobo rotate

clockwise. Effects can be added to any attribute or attribute family and from that point

onward in the show, the parameters of the effect track, just like any other attribute

value.

oBusking - With Palette's unique approach to storing entire looks, rather than just

levels, the slider panels become incredibly flexible tools to busk shows live. The setup

and operation is far faster than other desks and core fade engine allows you to build

up extremely complex looks and then tear them back down to their primitives in any

order.

oMove In Black - Never again worry about manually marking your moving lights so you

don't see unwanted live moves on stage as cues come up without being limited to

global parameter timing. Each cue possess its own MIB timing as well as MIB

Suppression.

oTiming parameters are extremely flexible, from individual attribute family's wait, fade

p7

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

and profile settings for every cue, to traditional cue part architecture and extending

into the very powerful Independent Timing of every attribute in every cue.

oUpdating Cues - It couldn't be made easier: Just press [UPDT] and Palette presents

you with a list of possible items to update given your most recent changes, including

the current cue, palettes used in the current cue, track-back cues or Looks that are

being controlled by slider panels.

oTrack Sheets - Examining what is going on in your show during editing sessions can

sometimes be very tedious. Palette's Track Sheets give you a clear idea of what is

moving when (intensities or attributes) and even tells you when it moved last.

oSafety Net Features - Tracking Backup, Mirrored Saves, Checkpoint Files and Recovery

allow you to program and operate your show in a worry free environment.

Tip of the Day

By default, the Tip Of The Day is turned on when you start up Palette. You can scroll through tips

by pressing the [S2] key on the desk and close the tip by either pressing [ENTER] or [UNDO]. It

is tempting to turn it off, but keep in mind that these brief tips were written to point out some of

the more subtle features Palette has to offer. You would have to do a lot of reading of the on-line

help or printed manual to get these hints.

You can read tips anytime by selecting Tip of the Day from the main Help menu.

On-Line Help

Why read the manual when it is all on-line. Every dialog box has context sensitive help by just

pressing the [HELP] button. Press [HELP] then any other button to get a description of its uses.

Press [HELP] twice to get the full help contents. The on-line help has advantage over the printed

manual as the hyperlinks allow you to jump around very quickly from topic to topic.

p8

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

The full and up-to-date manual is also available on-line at www.strandlighting.com

Palette Control Panel

When you are running the main software and no moving lights are selected, you can press [S4]

to reach the processor’s Control Panel. The Control Panel gives you access to general functions

like changing the date and time, adjusting how the trackpad works and setting up your network

connections. Palette comes loaded with useful software like Notepad, Internet Explorer and MS

Media Player. Listen to MP3s or CD while you work. You can also launch a hardware test to make

sure all your buttons, LEDs and sliders are working properly from the Control Panel.

Getting Technical Support

p9

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

For technical support, please refer to the Strand Lighting Offices and Service Centres

p10

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

About Palette

Two basic styles of lighting consoles have evolved since computerized consoles were

introduced in the early 1970s. These two styles can best be described as “tracking” and

“preset”.

Preset consoles record cues the way manual preset consoles do. On a manual preset console,

the user sets up a look on an active set of faders, then sets up the next look on an inactive

set of faders, and then uses cross-faders to fade from one look to the next. In a computerized

preset console, these looks are saved as cues, but each channel needs to be told what to do

in each cue, and cue execution can only crossfade from one cue to another.

With a tracking console, when a cue brings a channel to a level, that channel stays at that

level until it receives a specific instruction to change levels. This level then tracks through all

subsequent cues until the level is increased or decreased by another cue. Tracking consoles

are capable of much more sophisticated and complicated effects than Preset consoles because

of their ability to have more than one fade executing at the same time.

Where does Palette fit in?

oPalette is a tracking console.

oPalette offers the techniques of tracking consoles in an easy-to-learn environment.

oThe Timing options in Palette are extremely flexible and easy to use. The interface for

changing simple times is as easy to use as a spreadsheet and allows adjustment on

individual attribute family's wait, fade and profile settings for every cue. Palette also

has a traditional cue part implementation that greatly reduces the number of

keystrokes necessary to maintain these typically complex cues. In very demanding

programming environments, Palette extends timing options with the very powerful

Independent Timing of every attribute in every cue.

oPalette deals with moving lights using Horizon Control's Universal Attribute Control

Model. This means that regardless of who manufactured the moving light and what

protocol it is using, it is presented to the user the same way. Cues are stored using

descriptions like "Blue", "3 RPM" and "11 Hz". This means that not only can you copy

attributes from one type of fixture in your rig to another with predictable results, you

can also swap your entire rig out for another and not have to re-program your cues.

oPalette uses a “Graphical User Interface” and replaces the hidden command structure

of the DOS-based tracking consoles with modern computer interfaces like menus and

dialog boxes. It can easily be understood and programmed by any computer-literate

operator. Since each dialog box control has a softkey accelerator, your hands are not

tied to the mouse. Pure keystroke syntax is not only possible, but quite often quicker

than competing consoles. On the flip side, there is no need to memorize a strict syntax

as the softkeys are always narrowing your choices to less than a dozen option. You can

read the dialog box from top to bottom like a book and quickly find the options you are

looking for, even resorting to the mouse if that suites you. Palette will never beep at

you and expect you to fix the command line.

oBecause Palette's design leverages on consumer based technology (such as readily

available operating systems, USB interfaces and Pentium® Processors) it allows lower

budget theatres with operators who are not full time employees to have the

p11

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

sophistication that has previously been reserved for only the biggest of professional

theatres using specialized and dedicated equipment.

oSince a standard operating system is used and the hardware interfaces with USB, you

already have your backup desk. In fact, you probably have over a dozen of them in

your facility.

The software is designed, written and owned by Horizon Control Inc.

See Also:

Universal Attribute Control

Tracking

Edits Track Forward

Blocking and Unblocking of cues

License

p12

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

System Capacities

The Palette system capacities outlined below represent the upper range of capacities the

program can support.

Output Devices

32,768 (1024 on physical console without

external output devices)

Control Channels

No reasonable limit - determined by

amount purchased

Cues

Unlimited

Cue Lists

Unlimited

Looks

Unlimited

Looks per page

Unlimited

Look Pages

Unlimited

Simultaneous Fades

Unlimited

Priorities

100 different priorities available for every

Cue List and Sub Master

Macro Buttons

12 pageable virtual

Remote Video

Five connections via XP machine on LAN

running PalettePC software

Portable Remote Focus Unit

Optional

Tracking Backup

Yes

Crash Recovery

Yes

ILS Architectural Button Stations

Optional with ILS Interface card

Browser Control

On local or networked Internet browsers

Show Control Programming

Full programming language using Macro

Scripts and the Lua language

SMPTE/MIDI Interface

Optional

Serial Out

Macros available to output RS232

commands

External Trigger Events

2 triggers on Palette hardware or ILS

buttons stations or contact closures

Telnet and Serial session

16 Com ports and multiple telnet session

available

p13

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

Astronomical & Time Event Clock

Yes

"No reasonable limit" means that the limit is determined the processor and RAM on the

system.

See Also:

About Palette

-o-

p14

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

The Universal Attribute

Control Model by

Horizon Control Inc.

"Simplicity, clarity, singleness: These are the attributes that give our lives power and

vividness and joy as they are also the marks of great art." - Richard Holloway

Communication and the expression of ideas is central to the art of lighting. Creating great

lighting is a team effort lead by the designer. The language a designer uses to communicate

with the team, and specifically the console programmer, is crucial to the process of creating

the art. The programmer, in turn, must then train the console in order to orchestrate the

lights to ultimately relay the intent of the designer to the audience. There is ample

opportunity in this process for misinterpretations to muddy the waters of communication.

More recently, and at a furious pace, moving lights have entered the theatre and the

multitude of options they provide has only complicated this process amplifying the

opportunity for 'miscue' of intent.

Not surprisingly, there has been an increasing necessity to simplify the process of moving

light control. Unlike the hard and fast rules that have existed for decades, a uniform language

for designers and programmers to use for describing moving light behaviors has been

non-existent. Moreover, the method used to communicate to lights has never been

standardized. The pioneering manufacturers of automated lighting equipment each

implemented different philosophies of control. More recently, generic moving light console

manufacturers have had issues with just covering the bases. It has been a challenge for some

to turn the lights on and make them move about. In all respects, these consoles were merely

outputting numbers, sometimes masqueraded by words to get the job done. Now that

automated lighting is no longer in its infancy, it is time for a fresh new approach on intelligent

lighting control. Horizon Control has risen to that challenge and this document will explain

how we have achieved that goal with our Universal Attribute Control Model.

See Also:

Controlling Moving Lights

p15

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

Definition

The heart of this technology is our Universal Attribute Control Model or UAC for short. It is our

method of standardizing the language of communication with respect to intelligent lighting

control.

Elevating the means of control to an higher layer allows designers to once again think of their

lighting fixtures as merely tools available to get the job done. As the theatre embraced

moving light fixtures, it reluctantly accepted all of the idiosyncratic methods needed to control

them. The designers found themselves constantly adapting to the language imposed on them

by the manufacturer. Gone were the days of simply asking for lights and photons would land

on the stage.

Lets go back to the advent of computer controlled lighting to examine the issues that plagued

communication in the theatre. Before computers entered the theatre, the most popular

dimmer controllers were known as road-boards. These large devices had individual handles

for each dimmer and designers would ask operators to move a handle to a position to set the

light level. These 'move' instructions were written down as cues and with each one executed

in succession you had a show. The advantage of this system (which was only realized fully

after the obsolescence of road-boards) was that each move could be controlled at different

rates and multiple moves could be executed simultaneously by different operators.

Computer control first appeared on Broadway in 1975 when Tharon Musser used the

Electronics Diversified LS-8 console on A Chorus Line. This new technology allowed for

unprecedented repeatability and a huge number of cues executed in record time. As

processing power was very limited, decisions had to be made on how to execute these fades.

The technology and code development tools of the day dictated that each channel would be

recorded in each cue. This greatly simplified the process of playing back a show, or more

specifically, jumping from scene to scene during rehearsals. Remember, in the old days of

road-boards, getting to any place at random in the show almost always meant starting from

the beginning and executing each cue to ensure accuracy. LS-8 and others could do this with

ease. Kliegl quickly followed with the Performance and Strand with Multi-Q and Broadway

converted to computer control seemingly overnight. People were blown away with the

apparent new flexibility that these computers offered.

These early computer control systems did not emulate road-boards, but rather manual preset

boards. What designers eventually figured out, given a bit of experience on these consoles,

was that they could not achieve the complex cue timing that two or three road-board

operators did in the past. As these preset consoles recorded every channel in every cue, they

only moved from state to state. This resulted in robotic or non-organic fades. It was only

when Strand introduced the Light Palette that the technological problem that plagued these

fundamental concepts was realized on a computer (in North America at least).

People everywhere (and since) have praised Light Palette for marrying designer's desires and

computer control by using a common language. Almost every controller that has been

accepted on Broadway since has used core concepts introduced by Light Palette. With the

advent of intelligent lighting, so many more parameters have entered the equation that the

language conventions that have evolved are discordant and technologically inadequate. The

language must be overhauled. Conventional lighting control just worked in 2-space; Intensity

and Time. That is not so with moving light control. There are many many more parameters.

Moving light control has long suffered from the lack of this common language that designers

and programmers and manufacturers could use. To date, intelligent lighting control has only

stumbled along, managing to keep up with an evolving technology and never experienced the

p16

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

sort of watershed event that occurred in the industry with the introduction of Light Palette.

The problem was compounded by that fact that industry leaders were extremely protective of

their intellectual property. There was no sharing of control protocols between lights and

controllers. Each manufacturer vigorously protected the methods they used to control their

fixtures and automated systems were sole-source. Only recently has the industry evolved to

the point where most believe that inter-operability is a good thing.

Horizon Control Inc. (HCI) is at the very leading edge of this new paradigm of lighting control.

For years now HCI has had members sitting on ESTA's Control Protocols Working Group and

we are actively involved in the development of new protocols such as ACN (ANSI E1.17).

Horizon Control pulls from over a decade of experience writing lighting control software and

members of the development team were pivotal in the evolution of computer visualization

software. People on our staff have worked on some of the largest shows ever mounted with

virtually every make and model of popular lighting control systems. Our desire to simplify and

revolutionize the fundamental methods that are used to control lighting is deep rooted in our

collective years of experience.

The result is one of the most highly effective developments of a technology that we call

'Universal Attribute Control'. The descriptions and examples in this document are taken from

the implementation of our ' Universal Attribute Control' as used by the Palette Lighting

Console.

Background

The earliest forms of computer control, though digital at their core, output an analog signal

between 0 and 10v. This in turn controlled the lights from no output to full intensity. Inside

the console, these numbers were generally stored using 8-bit bytes, giving 256 steps of

resolution. With the advent of moving light systems, the resolution was doubled to 16-bit,

providing 65536 steps of resolution. Computers then calculated fades that produced a

one-to-one relationship between the 65,000 steps directly to motors that moved the light

from, say, pan-stop to pan-stop. This concept persisted for years and, given a specific

controller tied to a specific lighting system, pre-programmed shows were reproduced faithfully

night after night.

The downfall of this method of control is that these numbers ([0-10], [0-255] or [0-65535])

mean very little in the real world. They are actually only significant when used with very

specific equipment. When applied to other equipment, these numbers mean very little at all,

and in fact are often meaningless. UAC's objective is to provide an intuitive programming

experience and a versatile control system that when played back can actually provide the

operator information about the system it is controlling.

UAC does this by porting the control to an 'abstract' layer. This has a number of benefits:

1. The 'handles' you use to control moving lights are more inline with what you would do

to manipulate conventional lighting.

2. The numbers and 'words' you use to build cues will actually mean something. You will

have an idea of what you can do with the lights and what is on stage by reading the

screen.

3. If you have mixed equipment, the methodology you use to communicate with your

entire rig is identical, regardless of the protocols defined by the equipment

manufacturers.

4. Building a set of looks with one group of lights in your rig can be copied to another

group, regardless of what type of lights they are.

The cues you have in your show file can be played back with any equipment.

One of the key things in Point #2 above that bears repeating is that UAC uses numbers and

p17

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

'words' to control lighting. You may claim that has been done for years with the use of

'named' palettes. For example, moving lights desks can use labelled position palettes to build

cues and the cue displays use these 'words' to make it easier to read. Don't lose sight of the

fact that palettes, like "Down Stage Center", are just place holders for a combination of

values between 0 and 65535. The words themselves do not mean anything to the desk (nor

do the numbers). They are just displayed on the screen for convenience. In contrast, with

UAC, the words do mean very specific things within the cue structure.

Some of the words used include:

o15 degrees of pan

orotate counter clockwise at 6 RPM

ostrobe at 9 hertz

othrust the shutter into the aperture of the fixture half way

oreset the fixture's motor control system

At show-time, these 'words' need to be converted into 'values' that the specified lighting

fixtures can use. The trick with UAC is that this conversion is figured out each and every time

GO is pressed (and not before). That means that the protocol, the mode, the model or the

manufacturer can be changed at any time. Moreover, each and every light, regardless of who

makes it, appears similar to the user, giving a more consistent experience when programming

a show.

Apart from the benefits described above, this method of controlling lights is not restricted to

traditional linear channels mapped to attributes on the fixture. Looking at a few examples in

Palette's implementation of this model will demonstrate the intuitive nature of describing

fixtures' attributes as opposed to traditional convoluted methods that sometimes group

completely unrelated behaviours on the same channel.

Pan and Tilt Example

The Home position for pan and tilt on most DMX Moving Lights is 50:50 (or 32767:32767).

This positions the light such that you will have maximum movement in each direction before

encountering a stop (pan-stop or tilt-stop). For a light that has a total pan range of 360

degrees, with the control channel set to half, you are sitting at 180 degrees. Taking the

control channel to full will move the light 180 off axis towards a stop. So, to summarize, a

value of 50% means Home, and a value of 100% means go to the pan-stop 180 degrees from

Home. Figuring out that 90 degrees is half way in between those two values is easy. That

would be 75%. And a 45 degree pan from Home is, again, half way between those two values

or 62.5%. That gets a little too complex for the programmer to calculate quickly.

To add to the complication, imagine you have another light in the rig that has a total pan

range of 540 degrees. Now the numbers you just figured out for the first fixture mean nothing

to this one. Worse yet, if you grab both of the fixtures and pan them in tandem, you would

get completely differing results:

p18

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

Using the same values (62.5%), the angles of pan are completely different. The beams of

light are not even close to parallel. You can see how this can be very frustrating if you have a

mixed rig. With UAC, the Pan attribute is represented in real-world units of degrees.

Therefore, when you talk to the light, you tell it to pan so many degrees:

Apart from having parallel beams of light from multiple fixtures, notice that there is no need

for the "=" sign. Forty-five degrees is forty-five degrees. This makes controlling a rig that is

made up of different types of fixtures easy to communicate with and easy to understand.

If you program the show using one type of fixture, then swap it for another, it is important to

remember that it is these real-world values (in this case, degrees) that are used when fading

cues, not the DMX values. The example below will demonstrate this with two cues. Cue 1 and

Cue 2 are programmed with a fixture that is capable of panning 540 degrees (-270 to +270).

Cue 1 takes the fixture to its pan-stop at +270 degrees. Cue 2 has it move (in 10 seconds) to

a position of pan +90 degrees.

p19

Palette OS v10

Strand Lighting

If we were to substitute this fixture out for a fixture that only has a total pan capability of 360

degrees and run the cue, a surprising, but predictable thing happens. When Cue 1 is active,

the fixture can't reach +270 degrees, so it stops at its pan-stop (+180 degrees). Then Cue 2

is executed, which is a 10 second fade to +90 degrees. For the first 5 seconds of Cue 2, the

fixture doesn't move. But, when the Live display on the screen reads +180 degrees, which is

half way through the cue, the fixture will start to move. When Cue 2 is complete, the fixture

will be resting at +90 degrees:

Since the Universal Attribute Control Model doesn't figure out DMX values until the very last

second, it can also alter the way in which the conversion is done at run-time, producing new

and exciting methods of transition during the fade from cue to cue. Various attributes, such

as position and color lend themselves very nicely to working in different ways. Color Space is

described in detail below, but let's examine how we can move from one place to another on

stage given two stored end places.

In this example, we are going to once again consider a moving head fixture as opposed to a

moving mirror. Moving head lamps achieve movement by physically moving the source and

lens train with two motors within a yoke. This Pan/Tilt relationship equates to a polar

coordinate system using azimuth and elevation. When you move in this coordinate system, if

Other manuals for ClassicPalette

2

This manual suits for next models

3

Table of contents

Other Strand Lighting Control Panel manuals

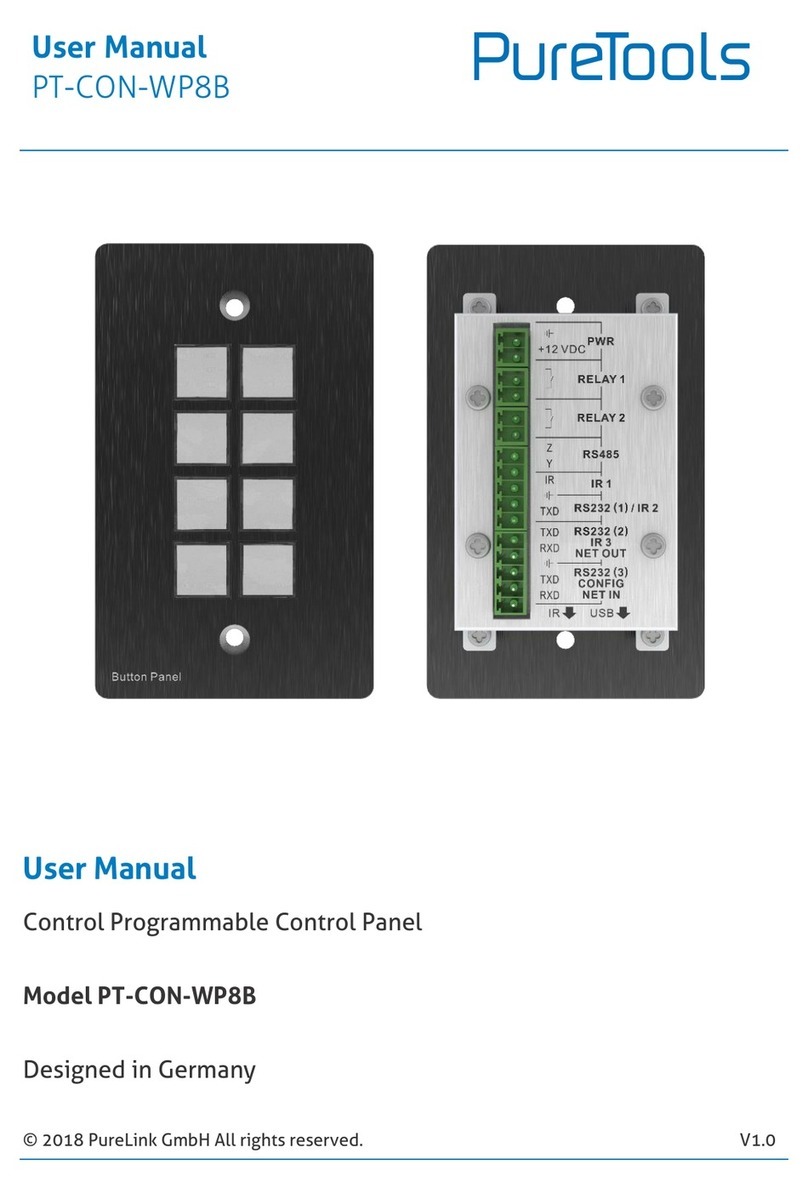

Popular Control Panel manuals by other brands

Pro-tec

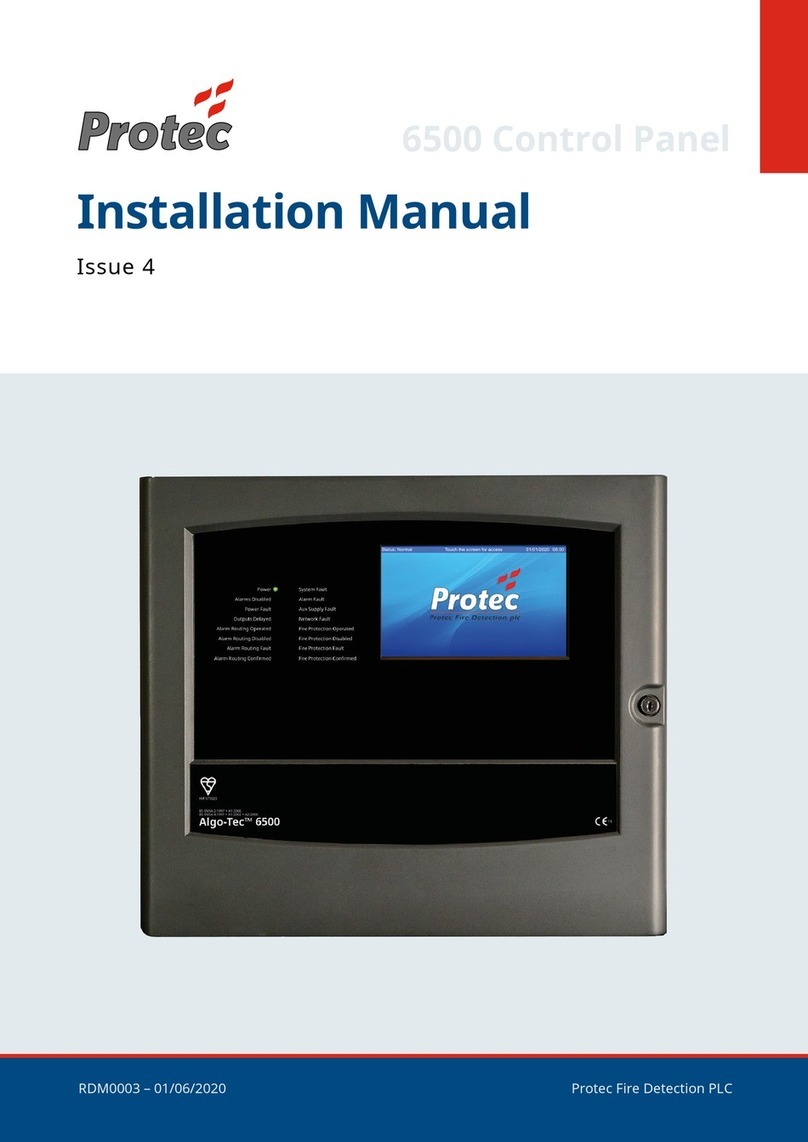

Pro-tec Algo-Tec 6500 installation manual

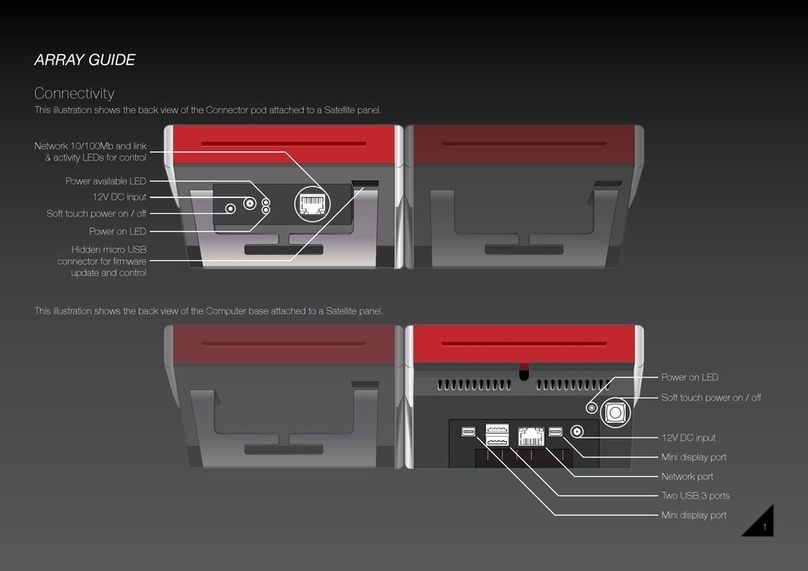

Hitech

Hitech ARRAY user guide

DM TECH

DM TECH FP9000E Installation and operation manual

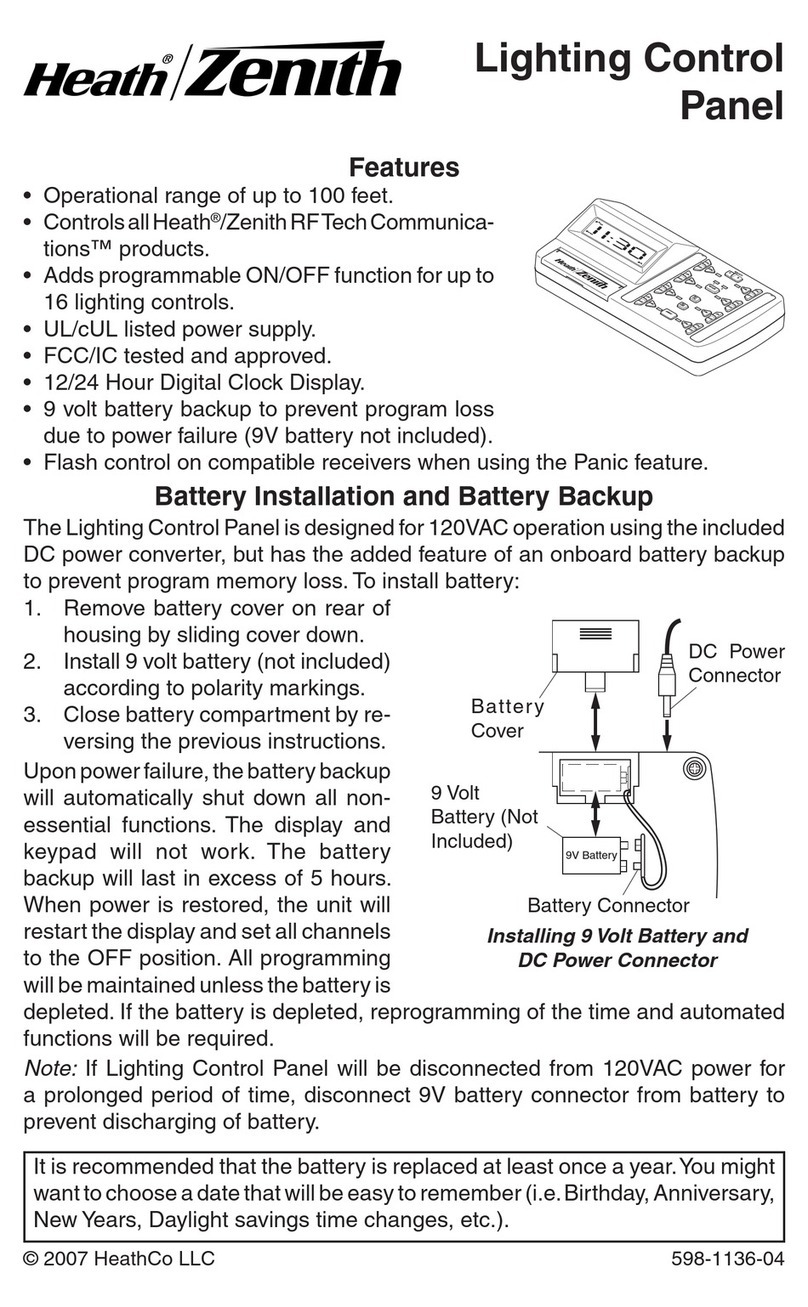

Heath Zenith

Heath Zenith Lighting Control Panel 598-1136-04 owner's manual

Keyautomation

Keyautomation EASY Instructions and warnings for installation and use

HIK VISION

HIK VISION DS-PK-LRT(433MHz) user manual