Texas Instruments TMS320 DSP User manual

Other Texas Instruments Computer Hardware manuals

Texas Instruments

Texas Instruments bq24650EVM User manual

Texas Instruments

Texas Instruments TUSB522P User manual

Texas Instruments

Texas Instruments TMAG5170D User manual

Texas Instruments

Texas Instruments TI-Nspire CX User manual

Texas Instruments

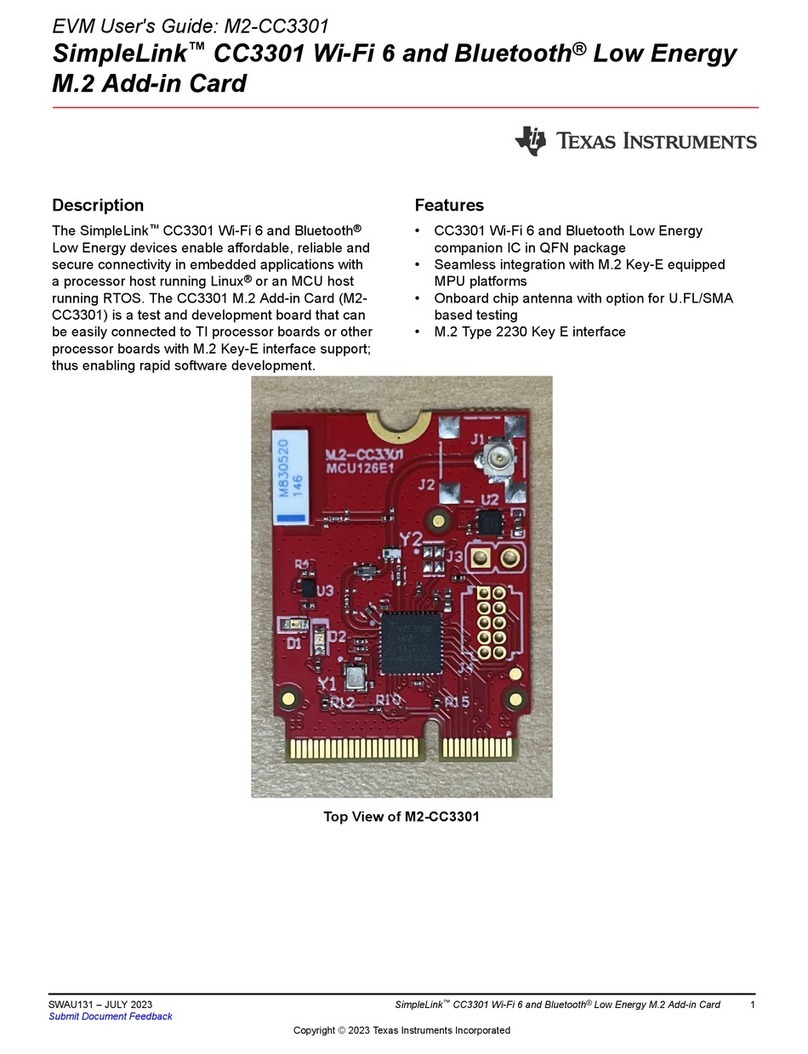

Texas Instruments SimpleLink CC3301 User manual

Texas Instruments

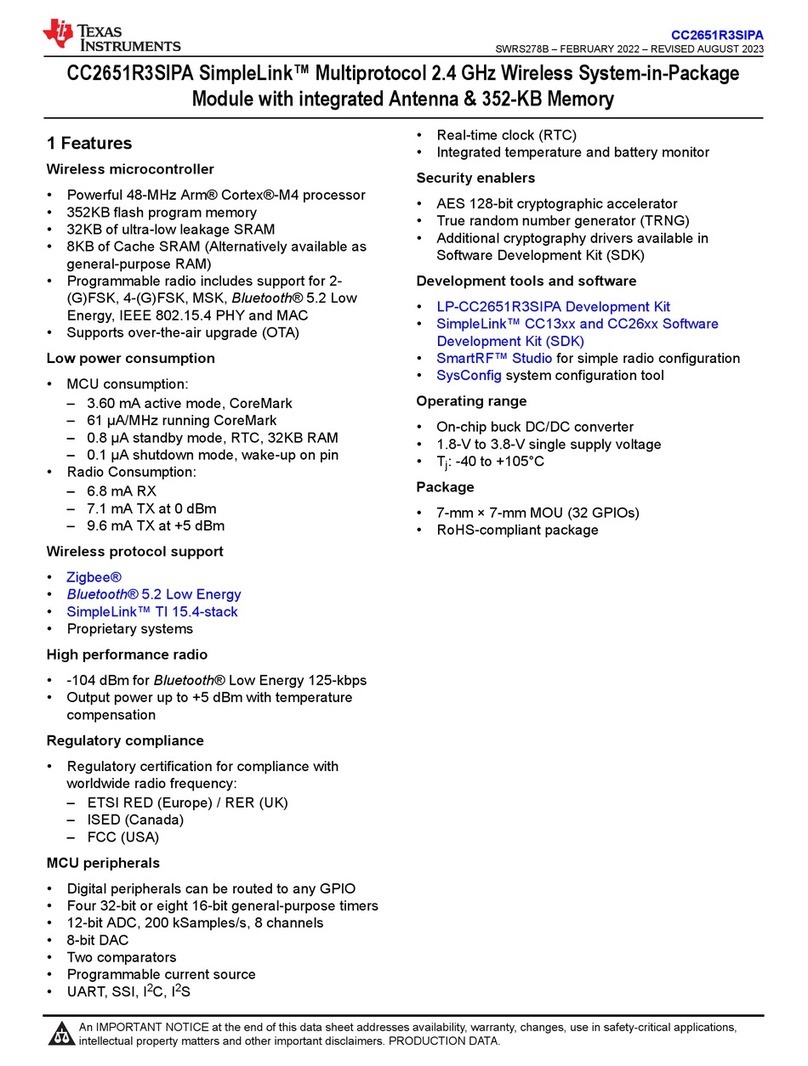

Texas Instruments SimpleLink CC2651R3SIPA User manual

Texas Instruments

Texas Instruments AM1808 User manual

Texas Instruments

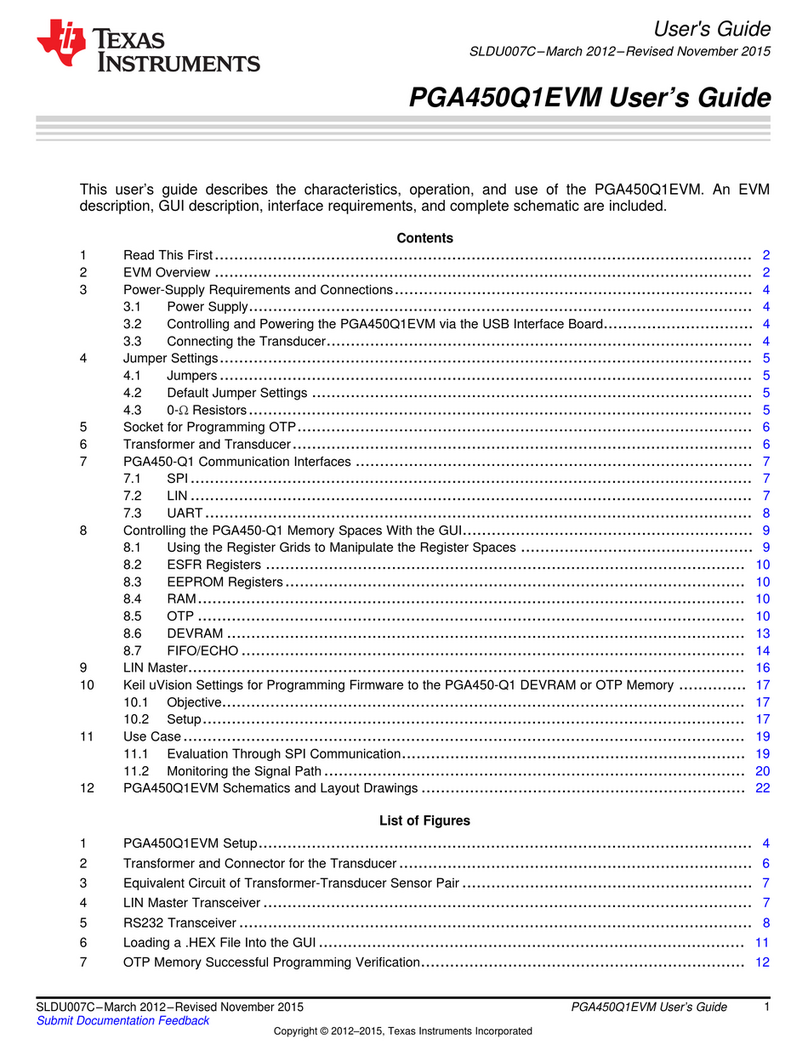

Texas Instruments PGA450Q1EVM User manual

Texas Instruments

Texas Instruments MSP-FET430X110 User manual

Texas Instruments

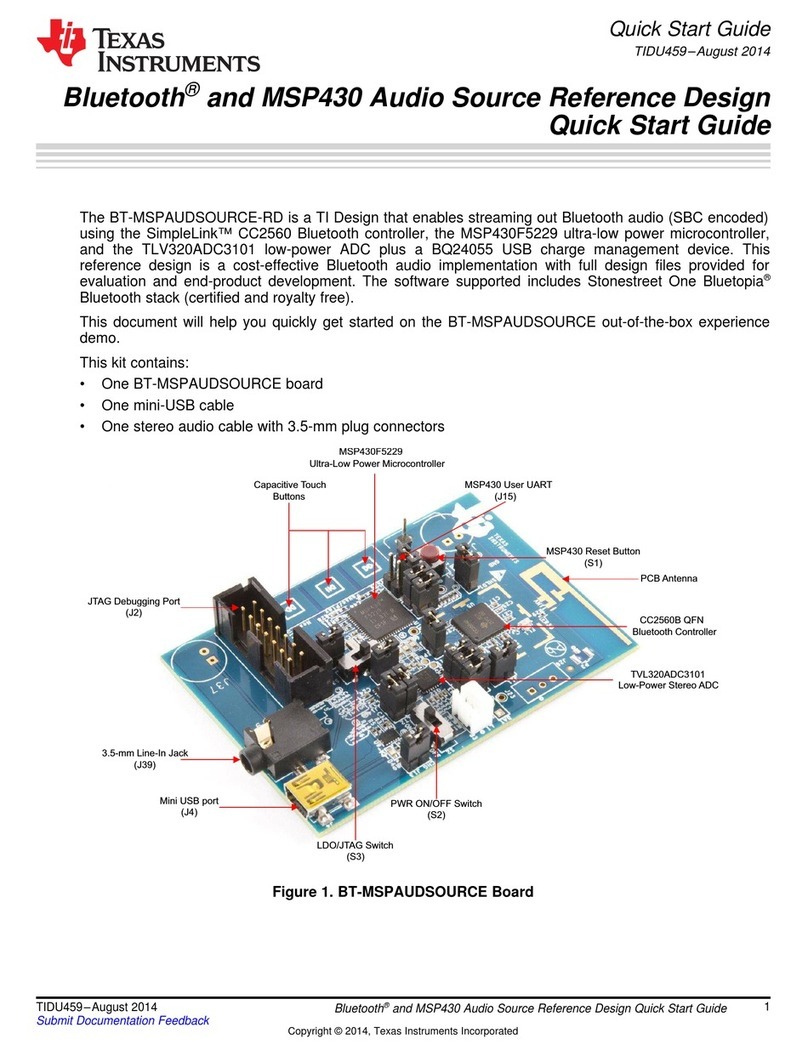

Texas Instruments BT-MSPAUDSOURCE-RD User manual

Texas Instruments

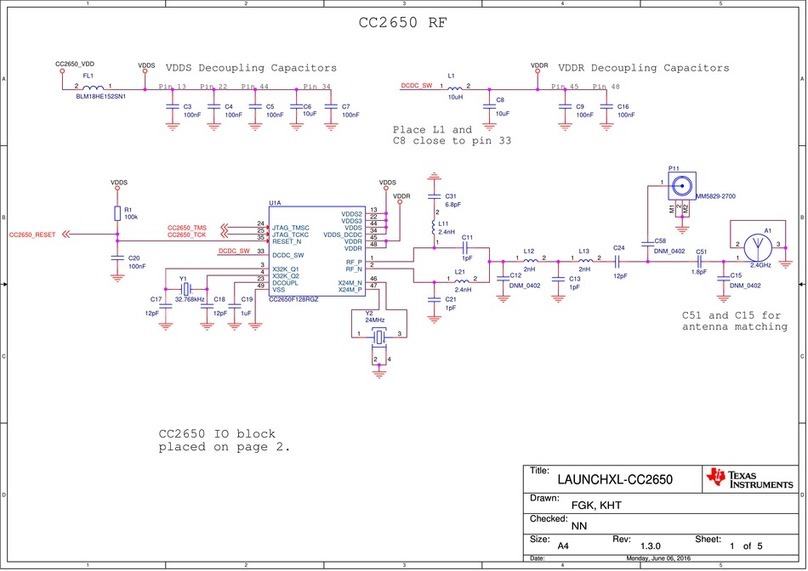

Texas Instruments LAUNCHXL-CC2650 User manual

Texas Instruments

Texas Instruments TUSB9260 User manual

Texas Instruments

Texas Instruments OMAP35 Series User manual

Texas Instruments

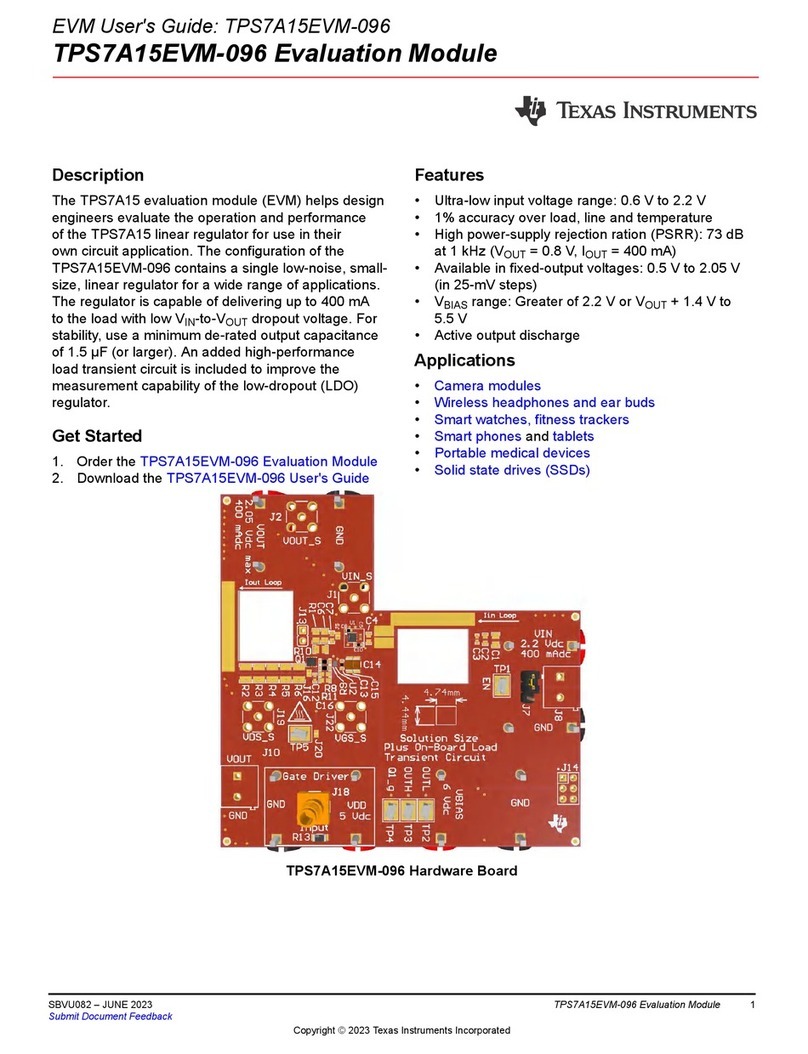

Texas Instruments TPS7A15 User manual

Texas Instruments

Texas Instruments MSP-FET430 User manual

Texas Instruments

Texas Instruments TMS320DM643 User manual

Texas Instruments

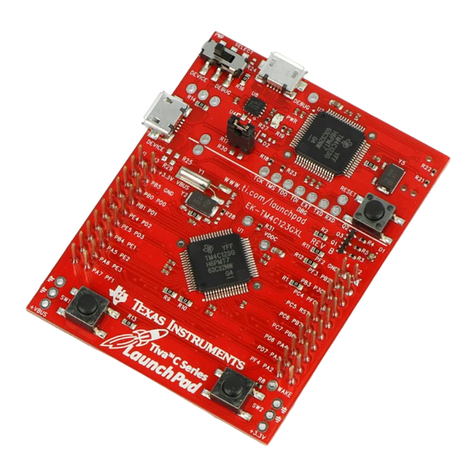

Texas Instruments Tiva C Series User manual

Texas Instruments

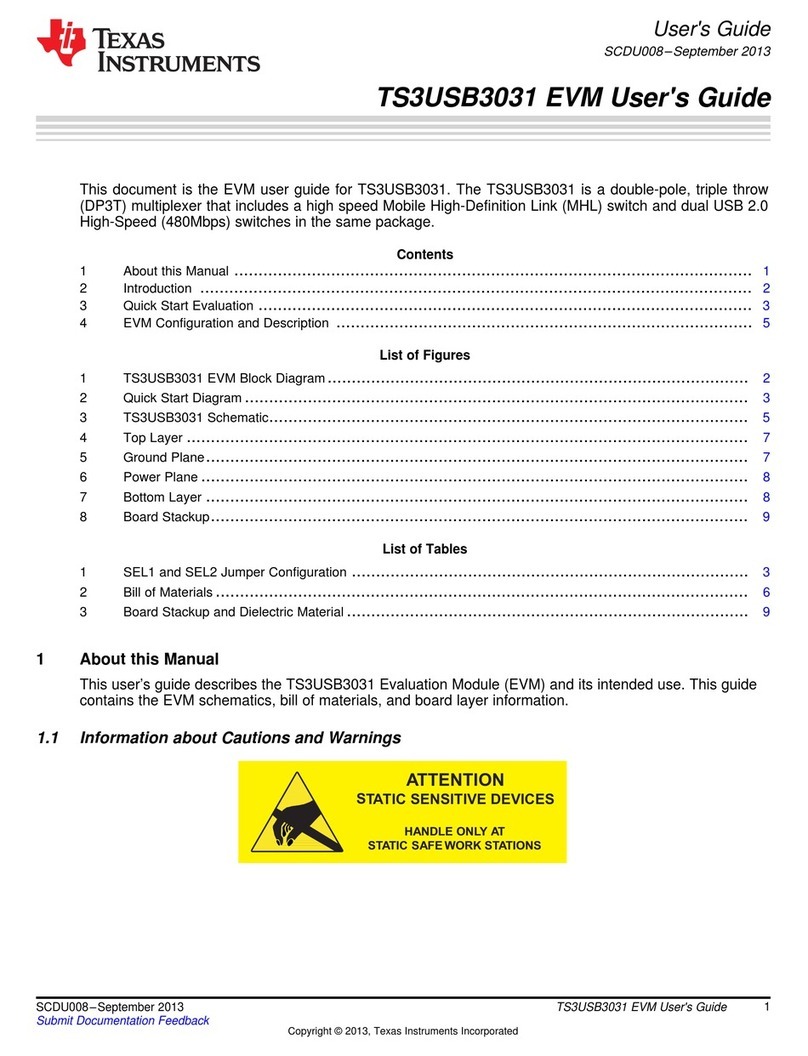

Texas Instruments TS3USB3031 User manual

Texas Instruments

Texas Instruments TMS320*2801 Series User manual

Texas Instruments

Texas Instruments TRIS TMS37122 User manual

Popular Computer Hardware manuals by other brands

Krüger & Matz

Krüger & Matz Air Shair2 owner's manual

Crystalio

Crystalio VPS-2300 quick guide

MYiR

MYiR FZ3 user manual

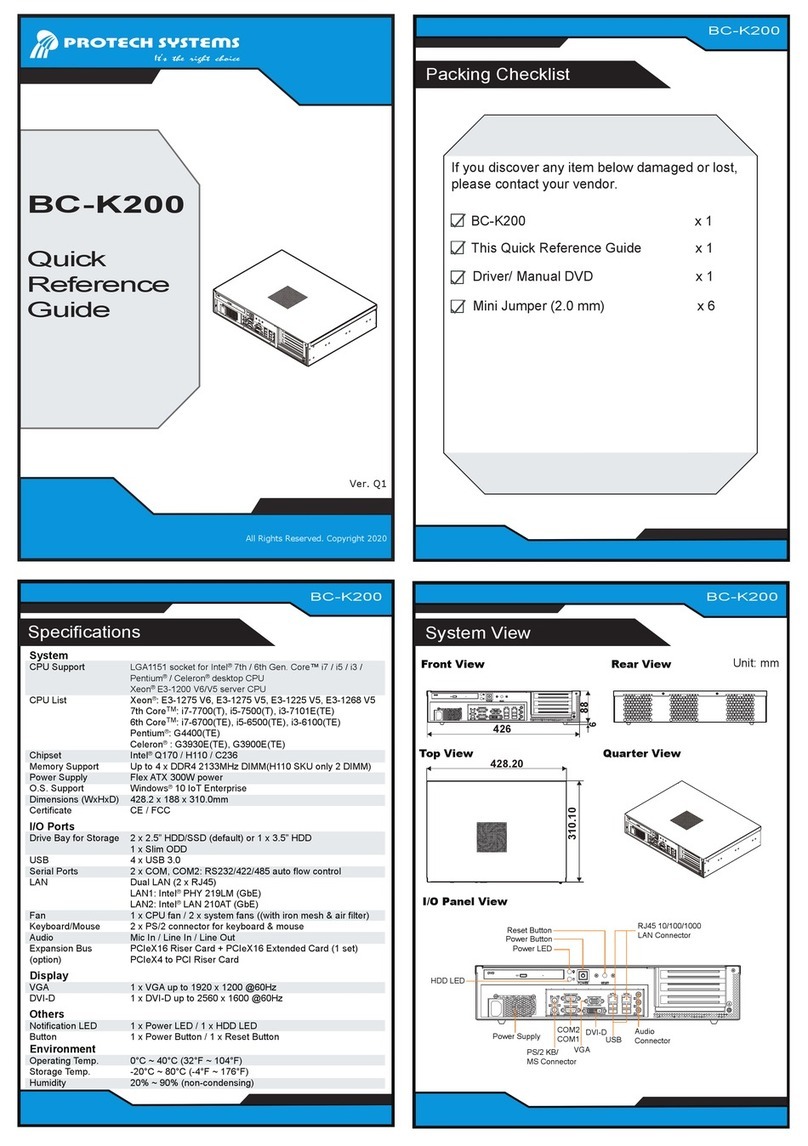

Protech Systems

Protech Systems BC-K200 Quick reference guide

Miranda

Miranda DENSITE series DAP-1781 Guide to installation and operation

Sierra Wireless

Sierra Wireless Sierra Wireless AirCard 890 quick start guide